More with Paul Maliszewski, author of Fakers.

Joseph: How do you categorize your book? Do you see it as literary journalism? As cultural criticism? As a kind of memoir?

Maliszewski: Can I categorize it as completed? I really don’t know. The longer parts of the book I always thought of as essays. But some of the shorter chapters began life as book reviews, although I hope they’re better written and more thoughtful than the average review, which too often consist just of summary. I sometimes thought of the book as literary criticism, since mostly what I do is read and analyze writing, trying to understand why it was put together the way it is and how it affects us and what we bring to our reading of it. You know, I assume, that nothing quite gins up book sales like an author saying he’s got a new batch of literary criticism. Categorizing is tough. Luckily for me, the publisher decided to slot the book as cultural studies. They know best.

Joseph: What other books are similar to yours? What literary tradition do you see your work fitting into?

Maliszewski: Two writers who come to mind are John McPhee and Renata Adler. I have exactly no business inserting my little book into such august company, but McPhee makes wonderful, often slyly humorous stories out of facts and Adler is a fierce and careful advocate. My writing aspires to the standards set by their work.

Joseph: What other projects are you working on?

Maliszewski: You remember those prayer stories I started writing in Martone’s class on the short-short story?

Joseph: You made a chapbook of those stories. I still have my copy, and I've shown it to about a gazillion students over the years as an example of the beauty of handmade books.

Maliszewski: I’m nearly done with that collection, which I’ve now taken to calling Prayers and Parables. I’ve been working on them longer than I have the pieces in Fakers. I’m so slow, Diana. I’m also working on a book with our friend Steve Featherstone, another survivor of Syracuse. That book is about Joseph Mitchell and his enormous collection of, for lack of a more inclusive word, stuff. Mitchell collected doorknobs and escutcheons, bricks and chunks of floor tile, everything—hundreds objects he sometimes salvaged from buildings slated for demolition or already reduced to rubble. Steve has taken photographs of the collection and I’m supposed to be writing an essay.

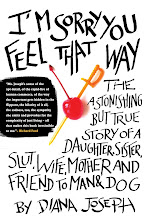

Now it’s my turn to ask you some questions. Fair is fair. In Fakers, I wrote some about the recent spate of fraudulent memoirs, from Frey and his A Million Little Pieces to Margaret Seltzer, the woman who invented a gang life for herself in Love and Consequences, to the fake Holocaust memoirs by Binjamin Wilkomirski (Fragments) and Misha DeFonseca, who, in Misha: Memoire of the Holocaust Years, claimed that as a child she walked across Europe and lived in the forests, among wolves. As the author of a memoir as well as—if I may—a wonderful fiction writer, did the unmasking of these shoddy memoirists cause you much worry?

Joseph: Worry about memoir’s dignity as an art form? Worry about if readers would question the validity of my stories? Actually, I worried about the writers of those fake memoirs. I worried about what was going on with Margaret Seltzer: Who is she, really, and what happened in her real life that caused to her invent this particular story? Why gang life? Why appropriate from a culture that seems so far from her own? Did she think her life was too boring? Did she think no one would be interested in the real Margaret Seltzer? I think that’s heartbreaking. I can speculate that she invented a redemption narrative, a survivor’s tale, because those memoirs sell, but that seems too easy. I can’t help but think it’s got to be more complicated. I guess I’ve got some amateur psychologist in me who wants to know what’s underneath: she fabricated a story, yes, but why this story?

Maliszewski: So you were never tempted to narrate that time teenaged Diana ran away from home, joined up with Barnum & Bailey, then left to climb Mt. Everest and ended up having to wrestle a tiger over some food?

Joseph: I told you to never speak of that.

Maliszewski: I know in your short stories you sometimes write from your life, using what happened as only a starting point. Surely, almost every fiction writer does this to some extent. When you’re writing an essay or working on this memoir though, do you find it difficult to write exclusively from life?

Joseph: I remember this essay where Flannery O’Connor is talking about writing her story “Good Country People,” how she didn’t know the Bible salesman was going to steal the lady PhD’s wooden leg until a few lines before it happened. And that’s what writing fiction does to me, too: it’s the what-happens that surprises me. I love the way characters can catch me off guard, do unexpected things.

But for me, the what-happens isn’t what’s interesting about writing essays. In essays, people have already done what they’re going to do, they’ve already said what they’re going to say. There’s no changing that. What I love is the thinking about why they’ve done it, why they’ve said it, what it means, why a reader should care.

Take this anecdote, for example. I could think all day on what it means, what it reveals about my son and me, what it says about power dynamics and competing philosophies. The boy and I recently got a kitten and while this sweet sassy ball of fluff has brought all this energy and light into the house, her presence infuriates our older cat. In fact, the older cat is so peeved that every night she hops into the kitten’s litter box where she leaves a big old nasty deposit, and—this is the best part—she doesn’t bury it. She just leaves it there to show the kitten: this is what I think of you. There’s a turf war taking place in our house. Territory is being claimed. Lines are being drawn. I look at that nasty mess in the litter box and see a metaphor. “Wouldn’t it be fantastic,” I asked the boy, “if we had that kind of power? If we could go to the bathroom, that most intimate space, at an enemy’s house and leave a little something there for him to find in the morning? Wouldn’t that send the clearest of messages?”

“It’s cat shit,” my son, the literalist, said. He's not as obsessed as I am with the search for meaning, but I'm going to give him time.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

.jpg)

8 comments:

As a forensic genealogist who built the research teams in both the Misha Defonseca and and Herman Rosenblat frauds, I am particularly interested in the response to Maliszewki's new book "Fakers."

The Publishers' Weekly review of "Fakers" seems obtuse and the Washington Post review reads like a verbal accounting sheet. More recent reviews seem to focus on some trivialized portion, such as the response to the exposure of Chabon or whether the reviewer agrees with statements that Maliszewki makes when distinguishing between satire and fraud. I'm wondering if there has been any in depth response to the issues raised. Although I have only read Maliszewki's interviews rather than the book, it seems that the book is an invitation to explore the issues more deeply. Yet, I get the feeling that the one theme that is common in the reviews is to close the book with a simplistic but comfortable summation.

That observation is aguably biased by my crash course in the publishing industry over the last year. News reports, articles and essays reflect difficulty with the depth of complexity in such fraud cases. Even Jill Lepore in the New Yorker completely puzzled me by tieing historiography and literature forms into the gender of the readership based on just superficial news coverage of Defonseca

and Seltzer.

Having provided many interviews, several articles and presentations on the Defonseca case I have struggled with the complexity of describing such frauds myself. However, the difference is that I have struggled to convey the details in a comprehensible fashion as opposed to simply picking out the information that is most understandable to me.

The response from the audience at every presentation is invariably centered on "How could Defonseca do this?" not why. It's recognition of the damage caused by fraud that evokes a moral outrage.

Several Belgian and French journalists have not shied away from the complexities in the Defonseca fraud, culminating in a Belgian documentary by Emmanuel Allaer. An English version is now available and I hope it will become a real educational tool. The film is a masterful exploration the issues and people damaged by the fraud.

The US press didn't have the same motivation to examine the Defonseca fraud, even though Defonseca's fraud longevity in Europe relied on destroying the original US publisher through massive lawsuits and smoke screens.

It has been suggested that Europe is ground zero for the Holocaust, and thus more of an outrage response, or that Defonseca was relatively unknown in the US compared to her iconic status in Europe.

I actually thought that the accidental timing of Seltzer's exposure influenced the US press to jump from a gleeful "journalists fact check, publishers don't," to a historical litany lumping so many literary frauds together, as though all of the same cloth.

However, with the Rosenblat case, after the publisher and Oprah fingerpointing, a literary fraud "fly over" recitation returns, along with shruggers who say "It's just a story."

My Canadian grandfather used to tell stories to us as kids that made my great grandmother upset. She didn't want him telling stories about our Native American ancestors. She was a "lady" who wore white gloves, silky dresses and little hats when she went to visit her cousin, a ranking Canadian

politician. There's actually some truth in the Native American ancestor stories, but there were many other stories from grandfather that were just entertainment. I use examples of discovering the truth behind family traditions when I talk about the Defonseca case - to illustrate how the

research methods also work for garden variety family mythologies as well.

Yet, Rosenblat's story telling has a lot in common with Madoff's. Over many years, Rosenblat and

Maddoff repeatedly looked people in the eye and appeared to be sincere. That's why such frauds are

called confidence games. The motive is to gain the victim's confidence and betray it for other purposes.

Madoff's billions and Rosenblat's illicit earnings not the same order of magnitude?

The real measure for their harm is how deeply they affected their victims. The Rosenblats became

icons of the Holocaust in the US, just as Defonseca did in Europe, eclipsing the survivors who give

true testimonies. Survivors who have to go through a virtual needle's eye to be able to come out

the other side of horrible experiences and live constructive lives. True testimonies that reveal

the reason we have to study and document systematized evil.

The Defonseca case initially presented several opportunities. Unmask the fraud. Demonstrate the methodology. Help those with real stories to use the same research methods to anchor their own

stories. My plan was to use the Defonseca case as a Sherlock Holmes style sidebar in a consumer

oriented "how to," using modern forensic genealogy methods to separate the wheat from the chaff for

general family history research.

I did not realize I would soon be working on many potential fraud cases, and seeing so many common

patterns. One humorous anecdote (as long as you're not the victim) stems from an email I got from a person on a cruise ship who was concerned that a woman on the cruise was being bamboozled by a

shyster with stories about his wealth, accomplishments and family history. As a matter of fact, I could document that the romancer was telling the truth about who he was. The real fraud was that he somehow talked his mistress into going on the same cruise with he and his wife. There's a germ of a novel in

that story. Maybe even a business opportunity for a service center on cruise ships to investigate claims in spontaneous shipboard romances. On second thought - fact checking is probably not the first thing that an enamored victim even wants to consider.

Many journalists have claimed that they fact check and publishers don't. Yet, journalists ran the Rosenblat story right up the flagpole. It was not easy to get that flag taken down.

In the Defonseca case, I was amazed at the US interrogations I endured, despite the Belgian investigative press confirmations. Even Wilkomirski's biographer, Blake Eskin, couldn't reconcile his suspicions when he interviewed me. Despite reams of referenceable documentation, there was lingering suspicion "Why did you do this?"

Because I can.

Suspicions are so often misplaced that frauds can still zip right past the truth squad.

In the glimpses that I can gather for Maliszewki's thoughts I see opportunities for more discussion and education. I hope he views challenges and confirmations equally as important.

I don't see that journalists, publishers or memorists should be lumped together any more than the

same literary fraud incantations should be regurgitated every time one is discovered. I don't see the public as suckers for the "misery literature" or that modern culture is too shallow.

Culture, as well as individual personality and memory, is full of mythology, archetypes, apocalyptic fears, parables, allegories, allusions, illusions and dillusions. Any of the symbolism that makes great fiction identifiable and lyrical like popular melodies, can also coexist with the facts.

Online discussions are repleat with "the problem" with memoirs, ranging from being fraught with

untruths and artistic license, to memory is imperfect or personal truths are more important than facts, and the "misery literature" hunger.

My own book is now changing shape. It's now about what we learn in the journey through historical research of the facts that also makes our own fictions more understandable. Those

tangled facts and mythologies could arise from what happened an hour ago or a few centuries ago.

No one is going to turn themselves into a Pavlovian dog experiment to ascertain where the tangles are technically delineated. I do think that there is room for an art form that recognizes the parallel universes we all live in, yet raises the bar for an anchoring in truth - and even satire.

A nephew of Abraham Maslow educated me in the satire of the Three Stooges and the Marx Brothers. I had previously thought the comedy just frustratingly stupid. Now I have a few favorite quotes.

But that is another essay.

Sharon Sergeant

I wonder if any of those fakers have thought about writing a memoir about why they faked it. "I Lied: Here's Why." I think it would be interesting reading. I don't know if they would necessarily regain any respect, but it would be interesting nonetheless.

Maybe that's their plan. Maybe they're just waiting for the coals to die down a little then they'll come out with a book explaining it all.

Hi Sharon--thanks for stopping by! Your comment brings up some interesting points.

Jorge: I wonder that, too!

Jorge, a number of fakers have come forward with explanations and apologias. Jayson Blair wrote a memoir. Stephen Glass wrote a closely autobiographical novel (his main character is named Stephen Glass). Clifford Irving wrote a book about concocting the autobiography of Howard Hughes. Savannah Knoop recently published a memoir about what it was like pretending to be JT LeRoy. Knoop was his physical likeness, not the author behind LeRoy's own books. And Michael Finkel wrote a book that, among other things, addressed his being fired for creating a composite character in an article he wrote for the New York Times Magazine. Of those five books, Finkel's is the most honest and genuinely searching. But then Finkel did little that compares to the more widespread and repeated fakery of Blair or Glass.

The back story for Misha Defonseca's US fraud is out. http://www.amazon.com/review/product/0615237517

I suspect that Emmanuel Allaer's Belgian documentary about Defonseca will be picked up in the US this year.

The back story for Rosenblat has been promised by his potential film producer, but neither have a great track record for the truth. It is a dark tale of deceit.

For my flower child generation, Truman Capote's "In Cold Blood" was a window into psychology that seemed to capture what was previously the province of novels - like Conrad's "Heart of Darkness" or Doestoyevski's "Crime and Punishment."

Interestingly, David Blixt author of THE MASTER OF VERONA, seems struck by the "truth stranger than fiction" Defonseca back story.

I hope the writers' community seizes the day and brings back a deeper exploration of the divide between our illusions and the realities.

Sharon Sergeant

The correct link for the Defonseca back story -

www.amazon.com/review/product/0615237517

Sharon

Not sure why the Amazon link is getting truncated but I'll just post the book id.

0615237517 Jane Daniel Bestseller

I love that Prayer Book--I've seen it in one of Diana's classes. Looking forward to Fakers, and then to the Prayer and Parables book.

Post a Comment