Tuesday, January 30, 2007

An excerpt:

Interviewer: Perhaps not only a better memory, but a clearer vision as well? Robert Olen Butler said recently that what an artist is supposed to do is not avert his eyes.

Hannah: That’s true. Those that don’t avert their eyes are the real artists. It is concentration, that’s what Dostoevsky said. Concentration is what the artist is about: he can look, and look, and look, and look. He carries no brief. He will tell you everything he sees. This sensibility will overcome every tendency to capsulize or moralize or philosophize; it is why, despite the themes and philosophy announced in behalf of an author by others, the actual art experience is much more whole. Flannery O’Connor can never be accounted for by her Catholicism. There is something rich and deep and strange in her that just doesn’t get on a theorist’s page—that just does not explain itself by outlines. It’s a special feeling.

I know some writers who really are just above making change, but they can tell a story. It has nothing to do with what will show up on an IQ test. They are just gifted in a certain way—even sometimes as an idiot savant. Writers maybe just stare, like a cow—just staring. Most people don’t stare. A writer is unembarrassed to just keep looking.

Tuesday, January 23, 2007

William Faulkner's Nobel Prize Speech

Our tragedy today is a general and universal physical fear so long sustained by now that we can even bear it. There are no longer problems of the spirit. There is only one question: When will I be blown up? Because of this, the young man or woman writing today has forgotten the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself which alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat. He must learn them again. He must teach himself that the basest of all things is to be afraid: and, teaching himself that, forget it forever, leaving no room in his workshop for anything but the old verities and truths of the heart, the universal truths lacking which any story is ephemeral and doomed--love and honor and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice. Until he does so, he labors under a curse. He writes not of love but of lust, of defeats in which nobody loses anything of value, and victories without hope and worst of all, without pity or compassion. His griefs grieve on no universal bones, leaving no scars. He writes not of the heart but of the glands.

Until he learns these things, he will write as though he stood among and watched the end of man. I decline to accept the end of man. It is easy enough to say that man is immortal because he will endure: that when the last ding-dong of doom has clanged and faded from the last worthless rock hanging tideless in the last red and dying evening, that even then there will still be one more sound: that of his puny inexhaustible voice, still talking. I refuse to accept this. I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail. He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance. The poet's, the writer's, duty is to write about these things. It is his privilege to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honor and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past. The poet's voice need not merely be the record of man, it can be one of the props, the pillars to help him endure and prevail.

Monday, January 22, 2007

Zadie Smith, on writing

...somewhere between a critic's necessary superficiality and a writer's natural dishonesty, the truth of how we judge literary success or failure is lost. It is very hard to get writers to speak frankly about their own work, particularly in a literary market where they are required to be not only writers, but also hucksters selling product. It is always easier to depersonalise the question. In preparation for this essay I emailed many writers (under the promise of anonymity) to ask how they judge their own work. One writer, of a naturally analytical and philosophical bent, replied by refining my simple question into a series of more interesting ones:

I've often thought it would be fascinating to ask living writers: "Never mind critics, what do you yourself think is wrong with your writing? How did you dream of your book before it was created? What were your best hopes? How have you let yourself down?" A map of disappointments - that would be a revelation.

Map of disappointments - Nabokov would call that a good title for a bad novel. It strikes me as a suitable guide to the land where writers live, a country I imagine as mostly beach, with hopeful writers standing on the shoreline while their perfect novels pile up, over on the opposite coast, out of reach. Thrusting out of the shoreline are hundreds of piers, or "disappointed bridges", as Joyce called them. Most writers, most of the time, get wet. Why they get wet is of little interest to critics or readers, who can only judge the soggy novel in front of them. But for the people who write novels, what it takes to walk the pier and get to the other side is, to say the least, a matter of some importance. To writers, writing well is not simply a matter of skill, but a question of character. What does it take, after all, to write well? What personal qualities does it require? What personal resources does a bad writer lack? In most areas of human endeavour we are not shy of making these connections between personality and capacity. Why do we never talk about these things when we talk about books?

Reading the rest is worth your time.

Click here.

Saturday, January 20, 2007

A Review of Norman's Mailer New Novel

Here's an exerpt:

FOR Mailer, a novelist fanatically committed to the truth, the problem of the ego’s relation to other people has been for many years now the problem of the narrator’s relation to his material. In his eyes, writing must be an authentic presentation of the self.

As Mailer sees it, great writing puts before the reader life’s harshest enigmas with clarity and compassion. “The novelist is out there early with a particular necessity that may become the necessity of us all,” he has written. “It is to deal with life as something God did not offer us as eternal and immutable. Rather, it is our human destiny to enlarge what we were given. Perhaps we are meant to clarify a world which is always different in one manner or another from the way we have seen it on the day before.”

And once you have authentically presented yourself in your writing, you can no longer practice the expedience of concealing yourself as a person. So Mailer the man has — sometimes not happily — transgressed social norms, just as his books have crashed through the boundaries of alien identity and literary genre. Yet for all the cross-pollination between his art and his life, Mailer has always insisted on true art as a form of honest living. The writer, as he once put it, “can grow as a person or he can shrink. ... His curiosity, his reaction to life must not diminish. The fatal thing is to shrink, to be interested in less, sympathetic to less, desiccating to the point where life itself loses its flavor, and one’s passion for human understanding changes to weariness and distaste.”

...

This restless vastness of Mailer’s ambition (“In motion a man has a chance”) is such that his “failures” are seminal, his professional setbacks groundbreaking. His willingness to fail — hugely, magnificently, life-affirmingly — expands artistic possibilities. Then, too, point to any contemporary literary trend — the collapse of the novel into memoir; the fictional treatment of actual events; the blurred boundaries of “history as a novel, the novel as history” (the subtitle of “The Armies of the Night”) — and there is Mailer, pioneering, perfecting or pulling apart the form.

.

Friday, January 19, 2007

An Interview with Michael Martone

An excerpt:

Since you've identified yourself as a formalist, I'm interested in how you define formalism in relation to your own stuff. Just because, reading the textbook definition of "formalism" there seems to be a real resistance to even being conscious of the extrinsic, in terms of the historical, etc. You don't seem to operate that way.

MM: No. When it comes to prose writing. There seem to be a lot of ways prose writing organizes itself, structures itself, gets itself into forms. And there are certain critics, say Bakhtin, who would say that there is no prose form called the "Novel." Instead, it's really made up of a kind of pastiche of all these other forms. You look at the early novels and they're made up of letters, or a diary of man whose trapped on an island, or they're autobiographies, or they're memoirs, or they're histories, or they're travel guides, or they're travel narratives. There's no thing, that is the novel, that is unlike every other kind of prose writing. That the novel itself is made up of all these different kinds of prose writing. So to me to be a formalist is to recognize these various modes of the human organization of language into prose styles. And be able to switch back and forth from one to the other depending upon the context of what you want to do.

So does your work typically evolve from content to a revelation of form? Or do you usually find yourself more fascinated with a particular form?

MM: That's a good question. A chicken-or-egg question. You know, right now a lot of what I'm working on is this book of fours. I was always interested in the four for a quarter pictures, the photo-booth pictures. I had my students do the photo-booth pictures and try to use the four shots to make some kind of narrative. And I began thinking about various fours. So I guess the form itself, or the arbitrary form, sort of leads for me and I'll find ways to connect it. One form, of course, is the narrative form and it has its own structure of ground, situation, vehicle, rising action, etc. etc. If you make the decision that you're not going to tell a story, or be narrative, how you organize becomes more prevalent.

Thursday, January 18, 2007

An Interview with Andre Dubus

Smolens: Is it possible that there's a change, not in fiction, but in the way fiction is perceived?

Dubus: You mean imaginative writing!

Smolens: There seems to be an impatience on the part of some readers.

Dubus: They're sometimes unwilling to grant the writer a certain freedom. I think they are poor readers. I mean, when I read I like to forget my name. I like to experience being another person-I get to love the character, if the writer is good. I learn something, and then I put the book down and I'm me again.I think there are some people who have strong opinions, and they get offended by what a writer says. They seem dictatorial to me. Sean O'Faolain wrote an introduction to a big anthology of short stories, and in essence, he said, "If you don't like a story, consider it your fault. And read it again." Then he went on to explain eloquently why it may be your fault. For instance, you may be in moral shock: these characters may do something you never considered doing.A while back I read about the actress Debra Winger in a profile Tom Robbins did for Esquire. He put it better than this, but the essential question he asked her was, "You're not really beautiful, so why are you so beautiful on the screen?" A hard question, which he stated politely. And her answer was, "The camera picks up the heart. To go before the camera you must open your heart, and get rid of all prejudices, all preconceptions, and be absolutely open. If you had twin sisters appear before the camera-where one did this and the other didn't-the camera would see it immediately." In effect, that was her response. To me, that's what writing is about, and that's what pure reading is about.

Smolens: We've previously discussed that a central problem in writers' workshops can be criticism that merely tells the writer how to rewrite the story, and that some writers bring a piece to the workshop and request just that: they want their fiction written by committee, so to speak.

Dubus: In my workshops we've discussed this, and there have been times when I've learned that I was not the only one who found it difficult to go back to my own work-that's how important this problem can be.In my workshop we started to have difficulties; I had this explosion, then we took the summer off. Then Chris Tilghman came to the house to discuss how we should be when we came back together. If you go into a room with eight or nine very good professional writers and ask them to read your work, you're going to get eight or nine very good ideas, all of which would work. But it wouldn't be your story; it might be a story you could write, but it might not be the story you should be writing.What we worked out for the new workshop-there were a number of new members who joined at that point-was that a writer reading should say, "I just want to hear about this. I'm concerned about the grandmother's character." Or the writer can say, "Go full bore and tell me whatever you want."Some people enjoy a good debate, of course, but I started wondering: what is the reason for two writers arguing about a third writer's work in the third writer's presence? Too often they were arguing for their own ideas. It was exhilarating, but I'm not sure it's always a good idea.

For more click here.

If you haven't read Dubus' collection The Times Are Never So Bad, you need to.

Wednesday, January 17, 2007

Steve Almond's 10 Guiding Principals for Writing About Sex

Steve Almond is the author of two story collections (My Life in Heavy Metal and The Evil B. B. Chow); a novel co-authored with Julianna Baggott (Which Brings Me To You); and a nonfiction book about his passion for candy (Candy Freak.)

Tuesday, January 16, 2007

Saturday, January 13, 2007

Anton Chekhov

Ernest Hemingway

Lillian Hellman

Joan Didion

Vladimir Nabokov

Harlan Ellison

Oscar Wilde

Susan Sontag

F. Scott Fitzgerald

William Faulkner

William Faulkner

William Faulkner

Sinclair Lewis

Norman Mailer

Virginia Woolf

Flannery O'Connor

Alice Walker

English 643 Fiction Workshop Spring 2007

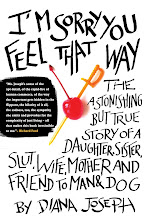

Diana Joseph Office: AH

English 643 Phone: 389-5144

Email: diana.joseph@mnsu.edu Hours: MTWT 11-12 & by appt.

Syllabus/other class documents: http://dianajosephsyllabi.blogspot.com

English 643: Seminar—Fiction Writing

Text

Diogenes, Marvin, and

Assignments See Schedule of Events for due dates

1. Craft Analysis/Presentation=50%

A. Select a story from any edition of Best American Short Stories between 1994—2006. The story you pick should be one you love. Make copies of your selection for everyone in the class—16 copies.

B. Define, then discuss and analyze ONE of the following elements of fiction as it relates to the B.A. story you selected. Support and illustrate claims with specific examples from the text; explain how and why the examples support your claim. Turn in your craft analysis to class on the day of your presentation.

Point of view Characterization Style Structure

Setting/place Tone Imagery Theme

2. Participation=50%

I define participation as your active engagement with the class, demonstrated through evidence of preparedness, and thoughtful contributions to discussions and workshops. Each of you will offer an assessment of your peers’ workshop responses; I will take this into consideration when determining participation grades.

Workshop Philosophy

This workshop differs from traditional workshops.

When we discuss a story, there won’t be talk about what we “like” or “don’t like.” There won’t be talk about what’s “good” or “bad”; there won’t be any value judgments. (This kind of feedback is hugely subjective and frequently confusing—like when six people love it, six people hate it, and one needs more time to think things over.) There won’t be advice on how to “fix” your story. (It’s your story, which means it’s your vision/version of the world, which means you should be the only one who can fix it.) There won’t be suggestions about what you “could” or “might” do. (I’m not interested in talking about writing that hasn’t been written.)

I am interested in what your story is about – the questions it raises, its themes, your artistic vision – and I’m interested in how your story is told, how its form reinforces its content. If writing is a series of choices, then what are the effects of these particular choices? If there’s an infinite number of ways to say something, then why are you saying it in this particular way? Why use first person instead of third person limited? What’s the effect of present tense over past? What are the story’s significant images and how do they create meaning? This workshop centers on describing and interpreting your use of the elements of fiction—and describing how each works with the rest to create unity, a singular effect, a vivid and continuous dream.

This approach demands work that’s more polished and developed than a rough first draft. Do not bring in work that is incomplete—it must have a recognizable beginning, middle and end. If you’re bringing in a chapter from a novel, please provide a brief description of your project. If you bring in sloppy work, don’t be surprised if there’s not much to say about it.

Class Policies

Do the work; don’t miss class; show up on time. Participation is 50% of your final grade. If you’re not here, you can’t participate. If you fail to turn in your story on the day it’s due, you lose your workshop spot. If you don’t come to class on the day of your workshop, it won’t be rescheduled. If you’re not here to give your Best American presentation, you can’t make it up. All coursework must be completed to pass this class. Assignments are tentative and subject to change.

Due Dates

1/24 Copies of your Best American selection due

Nyberg, “Why Stories Fail,” 221; Stern, “Don’t Do This,” 230;

1/31 Workshop story due

Best American—Bigalk and Cole

Surmelian, “Scene and Summary,” 164

2/7 Best American—Davis and Dunnan

Workshop

2/14 Best American—Engesether and Faul

Workshop

2/21 Best American—Hooper

Madden, “Point of View,” 248

Workshop

2/28 AWP

3/7 Best American—Irmen

Workshop

3/14 Spring Break

3/21 Best American—Johnson

Workshop

3/28 Best American—Khoury

Workshop

4/4 Best American—Lacey

Workshop

4/11 Best American—Miller

Workshop

4/18 Best American—Rolfes

Workshop

4/25 Best American—Starkey

Workshop

5/2 Best American—Vercant

Workshop

Name________________________________________________________________________English 643

On a scale of 1-10, rate the time/effort you estimate each student put into your workshop critique. Use the back of this sheet for further comments, if necessary.

1. Bigalk, Kristina M

2. Cole, Antoinette K

3. Davis, Andrew S

4. Dunnan, James W

5. Engesether, Marc R

6. Faul, Jade A

7. Hooper, Catherine A

8. Irmen, Ami M

9. Johnson, Bryan E

10. Khoury, Elysaar

11. Lacey, Kathleen N

12. Miller, Dodie M

13. Rolfes, Luke T

14. Starkey, Danielle M

15. Vercant, Matthew C

English 340 Form and Technique Spring 2007

Professor Diana Joseph Office Hours: MTWTH 11-12 & by appt.

MW 12-1:45 AH 310 Office: Armstrong Hall

Email: diana.joseph@mnsu.edu Phone: 389-5144

Syllabus/other class documents: http://dianajosephsyllabi.blogspot.com

English 340: Form and Technique in Prose

This course studies the technical underpinnings of prose genres. Through lectures, readings, class discussions, exercises in imitation, and workshops, we will examine the relationship between form (how the story is told) and content (what the story is about.) Specifically, we will pay close attention to technical matters including point of view, characterization, setting/place, tone, style, imagery, structure, and theme.

Required Texts and Materials

On Writing Short Stories. Ed. Tom Bailey.

3-ringed binder

$ for copying expenses

Assignments

1. Exercise Notebook=50%

Each class day, I’ll give you an exercise. You’ll begin it in class and complete it on your own time. These exercises must be typed and double-spaced and placed in a 3-ringed binder. Keep track of your work—when I collect the exercise notebook I’ll check for all exercises and prompts assigned throughout the semester and all workshop revisions AND I’ll assess according to the strength of the work; evidence of your effort; effectiveness of your revision; and originality.

2. Participation=25%

Participation is not merely showing up for class—that’s called attendance. I define participation as your active engagement with the class demonstrated through thoughtful contributions to class discussion, evidence of preparedness, and helpful feedback during workshops. Because this class relies so heavily on participation, you can’t sit silently and expect to do well (that’s called intellectual freeloading.) But I also don’t want one voice to dominate class discussions. Expect to listen as much as you talk. I don’t want to give reading quizzes so do the readings. Finally, each of you will offer an assessment of your peers’ workshop responses; I will take this into consideration when determining participation grades.

3. Justification Paper=25% Due on Finals Day

This is an 8-10 page formal essay in which you explain the relationship between form and content in your own work and defend your craft choices. Support and illustrate your claims with specific examples from work you produced for this class. If it helps support your case, refer to the work we’ve discussed in class.

Workshop Philosophy

We’ll workshop your exercises, with an interest in what your piece is about, and in how it’s told, and how its form reinforces its content. If writing is a series of choices, then what are the effects of these particular choices? If there’s an infinite number of ways to say something, then why are you saying it in this particular way? Why use first person instead of third person limited? What’s the effect of present tense over past? What are the story’s significant images and how do they create meaning? This workshop centers around describing (and interpreting) your use of the elements of fiction—and describing how each works with the rest to create unity, a singular effect, a vivid and continuous dream.

As a workshop participant, you must read the drafts up for workshop. You’re expected to write feedback, positive and critical, on the manuscript(s), and you should have suggestions in mind for class discussion. Expect to be called on.

Workshops are a give-and-take experience. If someone fails to provide evidence of reading and analyzing the strengths and weaknesses of your draft, then you’re not obligated to give that individual much feedback, either. But if someone gives a reading that shows time, effort, and thought – whether or not you agree with the comments – then you owe that person equal consideration. Workshops are about giving what you get.

Finally, workshops are not about egos – fragile, super, or otherwise. Workshops are not about being defensive, nor are they about hurling insults. Workshops are about the text, locating its strengths and weaknesses, and finding ways to make it stronger. Be critical, but be constructive.

Class Policies

Each absence over 3 will lower your final grade by 5%. I do not distinguish between excused and unexcused absence.

Participation is 25% of your final grade; if you’re not here, you can’t participate. If you fail to turn in workshop material on the day it’s due, you lose your workshop spot—and participation credit. If you don’t come to class on the day of your workshop, it won’t be rescheduled—and you lose participation credit. Frequent tardiness will affect your participation grade.

All coursework must be completed to pass this class.

Writing done for this class is considered public text.

Assignments are tentative and subject to change.

Academic dishonesty will not be tolerated; it may result in failure of the class.

I’m available for help outside class during my office hours or by appointment.

Due Dates

1/16 “Girl,” 306

1/18 “All the Way in

1/23 “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” 347

1/25 “The First Day,” 286

1/30 Exercise Packet Entry Due

2/1—2/22 Workshop

2/27 “Cathedral,” 108

3/1 No Class

3/6 “

3/8 “Home,” 410

Exercise Packet Entry Due

3/13—3/15 Spring Break

3/20—4-12 Workshop

4/12 Exercise Packet Entry Due

4/17—5/3 Workshop

Your Name___________________________________________________________________English 340

On a scale of 1-10, rate the time/effort you estimate each student put into your workshop critique. Use the back of this sheet for further comments, if necessary.

1. Bigham, Kellie J

2. Brummund, Andrea J

3. Chermak, Briana C

4. Engler, Aaron C

5.

6. Franzen, Adam P

7. Hamilton, Matthew J

8. Hammers, Eric R

9. Hart,

10. Hickey, Janel M

11. Klein, Nathan J

12. Lonnquist, Carl D

13.

14. Mariette, Jacob K

15. Martin, Tim M

16. McCorquodale, Brian M

17. Moeller, Heather A

18. Murray, Thomas E

19. Nerison, Bobbie

20. Peters, Brittney E

21. Schacht, Lindsay N

22. Schmitt, Daniel

23. Tyson, James R

24. Wayne, Tiffany L

25. Zierhut, Katie M

English 343 Fiction Workshop Spring 2007

Professor Diana Joseph Office Hours: MTWTH 11-12 & by appt.

MW 12-1:45 AH 310 Office: Armstrong Hall

Email: diana.joseph@mnsu.edu Phone: 389-5144

Syllabus/other class documents: http://dianajosephsyllabi.blogspot.com

English 343: Fiction Workshop

This is an introductory-level fiction workshop. Through close reading of literary short fiction, we will study elements of craft. Through a variety of writing exercises and prompts, we will practice our craft.

Assignments

1. Story Journal=25%

You will regularly receive writing exercises and prompts. You’ll begin many of these in class while some will be assigned for outside of class. These exercises must be typed and double-spaced and placed in a 3-ringed binder. Keep track of your work—when I collect your story journal, I’ll check for all exercises and prompts assigned throughout the semester. I’ll assess according to the strength of the work; evidence of your effort; and originality.

The full length story you’ll workshop toward the end of the semester will come from the entries in your story journal. In the meantime, we’ll workshop individual exercises as a way to jumpstart your writing process, generate ideas, and help you develop a full length story.

2. Two Self-Assessment Essays, each=25%

I don’t grade creative work; I do grade your ability to explain what you’ve come to understand about craft. Twice during the semester – once around mid-terms, and once by Finals Day – you will turn in a reflective narrative essay. In it, you’ll need to describe:

a. what you’ve learned about crafting fiction from the assigned readings

b. what you’ve learned about crafting fiction from the workshops

c. what participating in workshops – both as a reader and as a writer – has taught you about writing

d. any other aspects of the course that have guided or enhanced your understanding of fiction

3. Participation

I define participation as your active engagement with the class, demonstrated through evidence of preparedness, and thoughtful contributions to discussions and workshops. Each of you will offer an assessment of your peers’ workshop responses; I will take this into consideration when determining participation grades.

Workshop Philosophy

We’ll workshop your exercises, with an interest in what your piece is about, and in how it’s told, and how its form reinforces its content. If writing is a series of choices, then what are the effects of these particular choices? If there’s an infinite number of ways to say something, then why are you saying it in this particular way? Why use first person instead of third person limited? What’s the effect of present tense over past? What are the story’s significant images and how do they create meaning? This workshop centers around describing (and interpreting) your use of the elements of fiction—and describing how each works with the rest to create unity, a singular effect, a vivid and continuous dream.

As a workshop participant, you must read the drafts up for workshop. You’re expected to write feedback, positive and critical, on the manuscript(s), and you should have suggestions in mind for class discussion. Expect to be called on.

Workshops are a give-and-take experience. If someone fails to provide evidence of reading and analyzing the strengths and weaknesses of your draft, then you’re not obligated to give that individual much feedback, either. But if someone gives a reading that shows time, effort, and thought – whether or not you agree with the comments – then you owe that person equal consideration. Workshops are about giving what you get.

Finally, workshops are not about egos – fragile, super, or otherwise. Workshops are not about being defensive, nor are they about hurling insults. Workshops are about the text, locating its strengths and weaknesses, and finding ways to make it stronger. Be critical, but be constructive.

Class Policies

Each absence over 3 will lower your final grade by 5%. I do not distinguish between excused and unexcused absence.

Participation is 25% of your final grade; if you’re not here, you can’t participate. If you fail to turn in workshop material on the day it’s due, you lose your workshop spot—and participation credit. If you don’t come to class on the day of your workshop, it won’t be rescheduled—and you lose participation credit. Frequent tardiness will affect your participation grade.

All coursework must be completed to pass this class.

Writing done for this class is considered public text.

Assignments are tentative and subject to change.

Academic dishonesty will not be tolerated; it may result in failure of the class.

I’m available for help outside class during my office hours or by appointment.

Due Dates

1/22 “Sarah Cole,” 53

1/24 “White Angel,” 229

1/29 “The Way We Live Now,” 569

1/31 Prompts Packet Entry Due

2/5—2/26 Workshop

2/28 No Class

3/5 “

3/7 “Wild Horses,” 96

3/12—3/14 Spring Break

3/19 “Death by Landscape,” 31

3/21 “Tall Tales in the

Prompts Packet Entry Due

3/26—4/16 Workshop

4/18 Full Length Stories Due

4/23 Story Journals Due

4/23—5/2 Small Group Workshops

Finals Day Self-Assessment Part II due

Your Name___________________________________________________________________English 343

On a scale of 1-10, rate the time/effort you estimate each student put into your workshop critique. Use the back of this sheet for further comments, if necessary.

1. Amen-Reif, Rissa J

2. Anderson, Kristen J

3. Anderson, Nicolette R

4. Anderson, Sadie L

5. Anson, Michaela J

6. Eldridge, Amber K

7. Fine, Katrina E

8. Flynn, Kaitlyn

9. Franzen, Adam P

10. Hamilton, Matthew J

11. Hardt, Joshua C

12. Hempel, Kerra M

13. Jacobs, Morgan A

14. Jensen, Tyler J

15. Johnsen, Christopher

16. Lay, Mitchell A

17. Lloyd, Sara M

18. Madden, Nathan J

19. Meyman, Cory J

20. Pedersen, Carlene R

21. Peregrin, Anthony J

22. Rein, Katie L

23. Turner, Joyoung C

24. Williams, Zachary J

25. Zierhut, Katie M

Thursday, January 11, 2007

Workshop Considerations

2. What is the story's theme?

3. What emotional response does the story provoke in the reader?

4. How has the writers used the tools of his/her craft to create that response?

5. List the story's sequence of events.

6. How many stories is the writer telling?

7. Describe the story's pacing. Where does it move quickly? Where does it move slowly? What creates that

effect? Does the story's pacing match up with its content?

8. What are the story's central metaphors/images? How can they be interpreted? Do they relate to the story's theme?

9. Examine the writer's use of summary and scene. Why does the writer tell what he/she tells and show what he/she shows?

10. How does the story move through time?

11. Where are the flashbacks? How many flashbacks are there? How long are the flashbacks? What function does each serve?

12. What point of view does the writer use? How closely is the P.O.V. aligned with the central character? Why is this P.O.V. the best possible choice for this story?

13. What is the story's setting? Does the setting contribute to the story's theme? How?

14. What is the psychic distance between the narrator and the event? How does that impact the narrator's ability to reflect?

15. Is the main character self-aware?

16. a. What are the main character’s external stakes?

b. What are the main character’s internal stakes?

c. How do these reveal the story’s philosophical stakes?

17. How does the story's language/level of diction

a. reveal character?

b. create a mood, feeling or atmosphere

c. establish a tone

18. Does the story's dialogue (direct and indirect) reveal character?

19. 1. How does the writer use the five basic senses?

a. Smell

b. Taste

c. Touch

d. Sound

e. Sight

i. To show setting?

ii. To reveal emotion?

iii. To trigger memory?

___________________________

For the writer:

20. What details, characters, plotlines, passages are non-negotiable? What do you refuse to cut? What can you heartlessly slash?

21. If you have to pay me twenty bucks for every word you write, where would you cut back on language?

.jpg)