Sunday, December 30, 2007

Wednesday, December 19, 2007

50 Stories I Love in Different Ways and for Different Reasons

1. Andre Dubus “The Pretty Girl”

2. Flannery O’Connor “Revelation”

3. Benjamin Percy “Refresh, Refresh”

4. Tobias Wolff “Smorgasbord”

5. Melanie Rae Thon “Necessary Angels”

6. Michael Martone “Dish Night”

7. Lorrie Moore “People Like That Are The Only People Here”

8. Debra Monroe “My Sister Had Seven Husbands”

9. Michael Chabon “Son of the Wolfman”

10. James Baldwin “Sonny’s Blues”

11. Kate Braverman “Pagan Nights”

12. F. Scott Fitzgerald “Winter Dreams”

13. Walter Kirn “Planetarium”

14. Stuart Dybek “We Didn’t”

15. Ernest Hemingway “The Big Two-Hearted River”

16. Anton Chekhov “The Lady with the Pet Dog”

17. Joyce Carol Oates “How I Contemplated the World from the Detroit House of Corrections”

18. Robert Coover “The Babysitter”

19. Mona Simpson “Lawns”

20. Raymond Carver “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love”

21. Dale Ray Philips “Why I’m Talking”

22. Pam Houston “How to Talk to a Hunter”

23. Chris Offutt “Old of the Moon”

24 Richard Yates “A Really Good Jazz Piano”

25. J. D. Salinger “To Esme, With Love”

26. Elyse Gasco “Mother (Not a True Story)”

27. Rick Bass “Cats and Students, Bubbles and Abysses"

28. Gordon Weaver "Imagining The Structure of Free Space on Pioneer Road"

29. Dan Chaon “Big Me”

30. Cary Holliday “Merry Go Sorry”

31. Michael Cunningham “Mister Big”

32. James Joyce “The Dead”

33. Franz Kafka "The Metamorphosis"

34. Alice Munro, "Miles City, Montana"

35. T.C. Boyle “Carnal Knowledge”

36. Barry Hannah "Testimony of Pilot

37. E. Annie Proulx “Brokeback Mountain”

38. Mary Gaitskill "Girl on a Plane"

39. John Barth “Night-Sea Journey”

40. Susan Minot “Lust”

41. Robert Boswell “The Darkness of Love”

42. John Updike “A & P”

43. Tim O’brien “How to Tell a True War Story”

44. Junot Diaz “The Sun, the Moon, the Stars”

45. Rick Moody “Boys”

46. Susan Sontag “The Way We Live Today”

47. Z.Z. Packer “Brownies”

48. Peter Ho Davies ”The Ugliest House in the World”

49. Toni Cade Bambara “The Lesson”

50. Sandra Cisneros “The Monkey Garden

Sunday, December 16, 2007

Friday, December 14, 2007

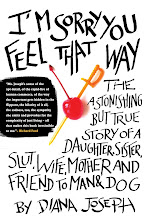

Have Any Of You Read This?

For an interview with Joshua Ferris, click here.

Tuesday, December 11, 2007

Monday, December 10, 2007

Saturday, December 8, 2007

Thursday, December 6, 2007

Wednesday, December 5, 2007

Tuesday, December 4, 2007

Monday, December 3, 2007

Sunday, December 2, 2007

Wednesday, November 28, 2007

Monday, November 26, 2007

What's Your Name?

You down with O.E.D. (Yeah you know me); Who's down with O.E.D. (All the homies)

Sunday, November 25, 2007

Saturday, November 24, 2007

Thursday, November 22, 2007

Sunday, November 18, 2007

Friday, November 16, 2007

Wednesday, November 14, 2007

Monday, November 12, 2007

Friday, November 9, 2007

"I've never had the good fortune of getting a clear idea in my head and then writing the damn thing down in one go. The only success I've had as a writer is by screwing up over and over and over. I'll write a story or a chapter 20 times before I start approaching what I think the story should be. And it is in that process of writing what I'm not supposed to be writing that I find my way to what I am supposed to be writing."

To read the rest, click here.

Sunday, October 28, 2007

Monday, October 22, 2007

Thursday, October 11, 2007

Nominees for the National Book Award.

I'm coming up on a literary extravaganza: I go to a Good Thunder reading tonight; a David Sedaris reading on Monday night; and on Tuesday, I'm in a workshop with my main woman Dorothy Allison .

Can I say I am super excited?!?

Tuesday, October 2, 2007

Saturday, September 29, 2007

Short Story Writers: READ THIS

September 30, 2007

Essay

What Ails the Short Story

By STEPHEN KING

The American short story is alive and well.Do you like the sound of that? Me too. I only wish it were actually true. The art form is still alive — that I can testify to. As editor of “The Best American Short Stories 2007,” I read hundreds of them, and a great many were good stories. Some were very good. And some seemed to touch greatness. But “well”? That’s a different story.

I came by my hundreds — which now overflow several cardboard boxes known collectively as The Stash — in a number of different ways. A few were recommended by writers and personal friends. A few more I downloaded from the Internet. Large batches were sent to me on a regular basis by Heidi Pitlor, the series editor. But I’ve never been content to stay on the reservation, and so I also read a great many stories in magazines I bought myself, at bookstores and newsstands in Florida and Maine, the two places where I spend most of the year. I want to begin by telling you about a typical short-story-hunting expedition at my favorite Sarasota mega-bookstore. Bear with me; there’s a point to this.I go in because it’s just about time for the new issues of Tin House and Zoetrope: All-Story. There will certainly be a new issue of The New Yorker and perhaps Glimmer Train and Harper’s. No need to check out The Atlantic Monthly; its editors now settle for publishing their own selections of fiction once a year in a special issue and criticizing everyone else’s the rest of the time. Jokes about eunuchs in the bordello come to mind, but I will suppress them.So into the bookstore I go, and what do I see first? A table filled with best-selling hardcover fiction at prices ranging from 20 percent to 40 percent off. James Patterson is represented, as is Danielle Steel, as is your faithful correspondent. Most of this stuff is disposable, but it’s right up front, where it hits you in the eye as soon as you come in, and why? Because these are the moneymakers and rent payers; these are the glamour ponies.

I walk past the best sellers, past trade paperbacks with titles like “Who Stole My Chicken?,” “The Get-Rich Secret” and “Be a Big Cheese Now,” past the mysteries, past the auto-repair manuals, past the remaindered coffee-table books (looking sad and thumbed-through with their red discount stickers). I arrive at the Wall of Magazines, which is next door to the children’s section, where story time is in full swing. I stare at the racks of magazines, and the magazines stare eagerly back. Celebrities in gowns and tuxes, models in low-rise jeans, luxury stereo equipment, talk-show hosts with can’t-miss diet plans — they all scream Buy me, buy me! Take me home and I’ll change your life!+I can grab The New Yorker and Harper’s while I’m still standing up, without going to my knees like a school janitor trying to scrape a particularly stubborn wad of gum off the gym floor. For the rest, I must assume exactly that position. I hope the young woman browsing Modern Bride won’t think I’m trying to look up her skirt. I hope the young man trying to decide between Starlog and Fangoria won’t step on me. I crawl along the lowest shelf, where neatness alone suggests few ever go. And here I find fresh treasure: not just Zoetrope and Tin House, but also Five Points and The Kenyon Review. No Glimmer Train, but there’s American Short Fiction, The Iowa Review, even an Alaska Quarterly Review. I stagger to my feet and limp toward the checkout. The total cost of my six magazines runs to over $80. There are no discounts in the magazine section.

So think of me crawling on the floor of this big chain store and ask yourself, What’s wrong with this picture?We could argue all day about the reasons for fiction’s out-migration from the eye-level shelves — people have. We could marvel over the fact that Britney Spears is available at every checkout, while an American talent like William Gay or Randy DeVita or Eileen Pollack or Aryn Kyle (all of whom were among my final picks) labors in relative obscurity. We could, but let’s not. It’s almost beside the point, and besides — it hurts.

Instead, let us consider what the bottom shelf does to writers who still care, sometimes passionately, about the short story. What happens when he or she realizes that his or her audience is shrinking almost daily? Well, if the writer is worth his or her salt, he or she continues on nevertheless, because it’s what God or genetics (possibly they are the same) has decreed, or out of sheer stubbornness, or maybe because it’s such a kick to spin tales. Possibly a combination. And all that’s good.What’s not so good is that writers write for whatever audience is left. In too many cases, that audience happens to consist of other writers and would-be writers who are reading the various literary magazines (and The New Yorker, of course, the holy grail of the young fiction writer) not to be entertained but to get an idea of what sells there. And this kind of reading isn’t real reading, the kind where you just can’t wait to find out what happens next (think “Youth,” by Joseph Conrad, or “Big Blonde,” by Dorothy Parker). It’s more like copping-a-feel reading. There’s something yucky about it.

Last year, I read scores of stories that felt ... not quite dead on the page, I won’t go that far, but airless, somehow, and self-referring. These stories felt show-offy rather than entertaining, self-important rather than interesting, guarded and self-conscious rather than gloriously open, and worst of all, written for editors and teachers rather than for readers. The chief reason for all this, I think, is that bottom shelf. It’s tough for writers to write (and editors to edit) when faced with a shrinking audience. Once, in the days of the old Saturday Evening Post, short fiction was a stadium act; now it can barely fill a coffeehouse and often performs in the company of nothing more than an acoustic guitar and a mouth organ. If the stories felt airless, why not? When circulation falters, the air in the room gets stale.

And yet. I read plenty of great stories this year. There isn’t a single one in this book that didn’t delight me, that didn’t make me want to crow, “Oh, man, you gotta read this!” I think of such disparate stories as Karen Russell’s “St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves,” John Barth’s “Toga Party” and “Wake,” by Beverly Jensen, now deceased, and I think — marvel, really — they paid me to read these! Are you kiddin’ me???Talent can’t help itself; it roars along in fair weather or foul, not sparing the fireworks. It gets emotional. It struts its stuff. If these stories have anything in common, it’s that sense of emotional involvement, of flipped-out amazement. I look for stories that care about my feelings as well as my intellect, and when I find one that is all-out emotionally assaultive — like “Sans Farine,” by Jim Shepard — I grab that baby and hold on tight. Do I want something that appeals to my critical nose? Maybe later (and, I admit it, maybe never). What I want to start with is something that comes at me full-bore, like a big, hot meteor screaming down from the Kansas sky. I want the ancient pleasure that probably goes back to the cave: to be blown clean out of myself for a while, as violently as a fighter pilot who pushes the eject button in his F-111. I certainly don’t want some fraidy-cat’s writing school imitation of Faulkner, or some stream-of-consciousness about what Bob Dylan once called “the true meaning of a pear.”

So — American short story alive? Check. American short story well? Sorry, no, can’t say so. Current condition stable, but apt to deteriorate in the years ahead. Measures to be taken? I would suggest you start by reading this year’s “Best American Short Stories.” They show how vital short stories can be when they are done with heart, mind and soul by people who care about them and think they still matter. They do still matter, and here they are, liberated from the bottom shelf.

Stephen King is the author of 60 books, as well as nearly 400 short stories, including “The Man in the Black Suit,” which won the O. Henry Prize in 1996.

Tuesday, September 25, 2007

FYI: In The Language of Publishers

“nice deal”: $1 - $49,000

“very nice deal”: $50,000 - $99,000

“good deal”: $100,000 - $250,000

“significant deal”: $251,000 - $499,000

“major deal”: $500,000 and up

Monday, September 24, 2007

Sunday, September 16, 2007

This and That

***

Sean Penn made a movie out of a book that I LOVE--I experienced this story first as a book-on-tape while driving across the country with my first husband, a man who related to the central character a little too intensely. But when/if this film comes to Mankato, I will want to see it. Anyone want to come with?

***

Then, after you read Into the Wild, you should then read Under the Banner of Heaven, another amazing book (you can read up on issues directly related to UtBoH here.)

***

Here's a good interview with Junot Diaz.

***

I love Paper Cuts, the NY Times blog about books, and I especially love Living with Music, its feature that asks writers to reveal what's on their iPod. Click here for Tom Perrotta, who's novel Little Children was far better than the film version, and the film version was pretty terrific.

Wednesday, September 12, 2007

Monday, September 10, 2007

Sunday, September 9, 2007

Saturday, September 8, 2007

Thursday, September 6, 2007

Tuesday, September 4, 2007

643 Prompt for Tuesday, September 4

You have REALLY bad gas at a funeral.

Courtesy of David Clisbee

Monday, September 3, 2007

Article, website, poem

* * *

101 Reasons to Stop Writing: Confronting the pandemic delusion of talent

* * *

Phemios

by Stephen Dobyns

Among the suitors, the poet was the worst—

drunk each night, cheating at dice, kicking

the old yellow dog. Even the suitors hated him—

a broken lute, amateur hexameters and singing

out of tune, but to send across the sea for another

was too great a bother, so the poet stayed on.

One would think when Odysseus showed up

to exact revenge the poet would be first to get it

in the neck, but as the hero stared down at this

piss-stained travesty of the muse, his verses

unpublished in the journals of Hellas, he decided

to let him live while slaughtering the rest. Who else

would spread his fame and sing of his noble victory,

albeit badly, who else would proclaim his deeds

from the marketplace to courtyards of kings?

Without this dabbler on the doorstep of the muse,

Odysseus' heroic action would be a vague whisper,

an unlikely rumor. So Odysseus sent him on his way

with gifts—fine linen to guarantee his invitation

to the best houses, sturdy sandals for the long road,

convincing hexameters, new strings for his lute.

Copyright © 2006 Stephen Dobyns All rights reserved

from Lumina

Sunday, September 2, 2007

For English 643: Week One #5 and Week Two #1

This concludes JW Dunnan's prompts.

Write a scene in which one character must communicate to another that his son has died without using any direct language:

NO:

"I'm sorry to have to tell you that your son is dead."

"Your boy's gone."

"This boy has ceased to be!"

Week Two/Prompt #1

for Monday, 9/3

Courtesy of David J. Clisbee

Write 1,000 words about attending a nudist prom.

********************************************************

REMINDERS:

Writers 1-5, don't forget to email me your favorite 1,000 word exercise for Wed. workshop by 5:00 today (for those of you who already have, thank you!) I will get those out to people by 5:30.

Writers 6-15, don't forget to make 16 copies of your favorite 1,000 word exercise and bring those copies to Wednesday's class.

Saturday, September 1, 2007

Thursday, August 30, 2007

643 Prompts

For Thursday, August 30

Write 1,000 words about this:

People often see complex personalities in their pets -- well beyond clichés like the loyal dog. Graft your pet's personality onto a human character.

Writing a Craft Analysis

A successful analysis will isolate a particular craft of craft – point of view, for example, or imagery, setting, tone, characterization, etc. – then discuss how it works to create unity, a singular effect, a vivid and continuous dream.

To write a craft anaylsis:

1. TYPE the passage that best illustrates the term you plan to discuss.

2. DEFINE the craft term you plan to discuss. If you say you’re talking about style, what specifically do you mean? If you say your analysis will cover a concept like theme (OR extended metaphor OR pacing OR the writer’s use of time), make sure you’ve first explained how, exactly, you understand that concept.

3. Make CLAIMS about the text: For example: Russell Bank’s use of third person in “Sarah Cole” operates as a way for the first person narrator to distance himself from events he’s ashamed of OR the short choppy sentences and emphasis on sensory detail in climactic moment of Michael Cunningham’s story “White Angel” heightens the dramatic tension and keeps the moment from lapsing into melodrama.

4. PROVIDE QUOTES from the passage that ILLUSTRATE/SHOW what you’re talking about.

5. EXPLAIN how and why the quotes you’ve selected illustrate your claims.

Wednesday, August 29, 2007

English 643 Prompt #3

Write 1,000 words based on this one word prompt:

Monster

I saw a series of short scenes by five playwrights who only had this one word theme. The results were varied and surprising.

Tuesday, August 28, 2007

English 643 Writers

Prompt #2

Base a 1,000 words around this randomly selected Neruda line:

"Still it would be marvelous to terrify a law clerk with a cut lily"

(Don't try to find the poem to get a context for it, create the context.)

Sunday, August 26, 2007

English 643 Writers

Write 1,000 words in response to this:

What's the best lie you've ever heard? Alternative - have your characters lie to each other.

Thursday, August 23, 2007

English 643/Graduate Fiction Workshop

English 643 E-Hours: T&F 9-12

Email: diana.joseph@mnsu.edu Office: Armstrong 201L

dianajosephsyllabi.blogspot.com Phone: 389-5144

Graduate Fiction Workshop

This workshop will operate differently from the traditional model. It does not focus on story as final product; you do not bring in a "finished" draft to find out whether or not it "works." Instead, this course uses the discussion of short, "unfinished" anecdotal pieces to explore a story's possibilities.

The class stresses close, careful reading and intensive writing. You'll write a thousand words a day, five days a week for fifteen weeks. Topics for writing will come out of prompts; each writer will be responsible for providing a week's worth of prompts. Every few weeks, we'll assemble a packet of these exercises. You should turn in the prompt you find most dynamic or intriguing, the one you're most excited about pushing further. We'll discuss your thousand word piece with an emphasis on craft, but also with the intention of locating the material's potential. Questions for discussion may include What is this piece's emotional center? What seems to be at stake? What are the metaphors? The conflicts? Based on what's here, who is the narrator?

More about My Workshop Philosophy

When we discuss a story, there won’t be talk about what we “like” or “don’t like.” There won’t be talk about what’s “good” or “bad”; there won’t be any value judgments. (This kind of feedback is hugely subjective and frequently confusing—like when six people love it, six people hate it, and one needs more time to think things over.) There won’t be advice on how to “fix” your story. (It’s your story, which means it’s your vision/version of the world, which means you should be the only one who can fix it.) There won’t be suggestions about what you “could” or “might” do. (I’m not interested in talking about writing that hasn’t been written.)

I am interested in what your story is about – the questions it raises, its themes, your artistic vision – and I’m interested in how your story is told, how its form reinforces its content. If writing is a series of choices, then what are the effects of these particular choices? If there’s an infinite number of ways to say something, then why are you saying it in this particular way? Why use first person instead of third person limited? What’s the effect of present tense over past? What are the story’s significant images and how do they create meaning? This workshop centers on describing and interpreting your use of the elements of fiction—and describing how each works with the rest to create unity, a singular effect, a vivid and continuous dream.

Class Materials

This is no required text for this class.

$ for photocopying/printing costs

Assignments

Participation=100%

This class depends entirely on your participation.

I define participation as your active engagement with the class, demonstrated through evidence of preparedness, and thoughtful contributions to discussions and workshops. I will also assess your participation by your completion of the following:

1. You’ll write 1,000 words a day, five days a week for 15 weeks. The writing will be in response to an assigned prompt. Don’t be surprised if I occasionally ask you to email me a file containing your prompts. I don’t want to police people, but I do want to provide an incentive to stay on track.

2. You’ll provide 5 writing prompts for the class. You’ll email your prompts to me by 5:00pm the Sunday of your week, and I will email them to the class.

3. Each of you will offer an assessment of your peers’ workshop responses; I will take this into consideration when determining participation grades.

Class Policies

Do the work; contribute in a thoughtful way to class discussions, but don’t monopolize. If you suspect you’re talking too much, you probably are. Missing more than one class results in dropping a full letter grade; if you’re not here, you can’t participate. Show up on time. No handwritten work will be accepted. All coursework must be completed to pass this class. Late work will not be accepted. Assignments are tentative and subject to change.

Your Name_________________________________________________________English 643

On a scale of 1-10, rate the time/effort you estimate each student put into your workshop critique. Use the back of this sheet for further comments, if necessary.

1. Arimah, Lesley

2. Benjamin, Jessica

3. Clisbee, David

4. Daly, Luke

5. Davis, Andrew

6. Dunnan, J. W.

7. Flynn, Thomas

8. Gatewood, Carrie

9. Grant, Richanda

10. Irmen, Ami

11. Johnson, Joshua

12. Langdon, Sarah

13. Slotemaker, Michael

14. Starkey, Danielle

15. Weerts, Matthew

Wednesday, August 22, 2007

English 343 Undergraduate Fiction Workshop

Interns: Jon Surdo E-hours: T&F 9-12

Bryan Johnson Office: Armstrong Hall 201L

Nathan Melcher Phone: 389-5144

Email: diana.joseph@mnsu.edu Online: dianajosephsyllabi.blogspot.com

English 343: Fiction Workshop

This is an introductory-level fiction workshop. Through close reading of literary short fiction, we will study elements of craft. Through a variety of writing exercises and prompts, we will practice our craft.

Assignments

1. Story Journal=25%

You will regularly receive writing exercises and prompts. You’ll begin many of these in class while some will be assigned for outside of class. These exercises must be typed and double-spaced and placed in a 3-ringed binder. Keep track of your work—when I collect your story journal, I’ll check for all exercises and prompts assigned throughout the semester. I’ll assess according to the strength of the work; evidence of your effort; and originality.

The full length story you’ll workshop toward the end of the semester will come from the entries in your story journal. In the meantime, we’ll workshop individual exercises as a way to jumpstart your writing process, generate ideas, and help you develop a full length story.

2. Two Self-Assessment Essays, each=25%

I don’t grade creative work; I do grade your ability to explain what you’ve come to understand about craft. Twice during the semester – once around mid-terms, and once by Finals Day – you will turn in a reflective narrative essay. In it, you’ll need to describe:

a. what you’ve learned about crafting fiction from the assigned readings

b. what you’ve learned about crafting fiction from the workshops

c. what participating in workshops – both as a reader and as a writer – has taught you about writing

d. any other aspects of the course that have guided or enhanced your understanding of fiction

3. Participation

I define participation as your active engagement with the class, demonstrated through evidence of preparedness, and thoughtful contributions to discussions and workshops. Each of you will offer an assessment of your peers’ workshop responses; I will take this into consideration when determining participation grades.

Workshop Philosophy

We’ll workshop your exercises, with an interest in what your piece is about, and in how it’s told, and how its form reinforces its content. If writing is a series of choices, then what are the effects of these particular choices? If there’s an infinite number of ways to say something, then why are you saying it in this particular way? Why use first person instead of third person limited? What’s the effect of present tense over past? What are the story’s significant images and how do they create meaning? This workshop centers around describing (and interpreting) your use of the elements of fiction—and describing how each works with the rest to create unity, a singular effect, a vivid and continuous dream.

As a workshop participant, you must read the drafts up for workshop. You’re expected to write feedback, positive and critical, on the manuscript(s), and you should have suggestions in mind for class discussion. Expect to be called on.

Workshops are a give-and-take experience. If someone fails to provide evidence of reading and analyzing the strengths and weaknesses of your draft, then you’re not obligated to give that individual much feedback, either. But if someone gives a reading that shows time, effort, and thought – whether or not you agree with the comments – then you owe that person equal consideration. Workshops are about giving what you get.

Finally, workshops are not about egos – fragile, super, or otherwise. Workshops are not about being defensive, nor are they about hurling insults. Workshops are about the text, locating its strengths and weaknesses, and finding ways to make it stronger. Be critical, but be constructive.

Class Policies

Each absence over 3 will lower your final grade by 5%. I do not distinguish between excused and unexcused absence.

Participation is 25% of your final grade; if you’re not here, you can’t participate. If you fail to turn in workshop material on the day it’s due, you lose your workshop spot—and participation credit. If you don’t come to class on the day of your workshop, it won’t be rescheduled—and you lose participation credit. Frequent tardiness will affect your participation grade.

All coursework must be completed to pass this class.

Writing done for this class is considered public text.

Assignments are tentative and subject to change.

Academic dishonesty will not be tolerated; it may result in failure of the class.

I’m available for help outside class during my office hours or by appointment.

Due Dates

8/29 “Sarah Cole,” 53

9/5 “White Angel,” 229

9/10 “The Way We Live Now,” 569

9/12 Prompts Packet Entry Due

9/17-10/8 Workshop

10/10 “Strays,” 542

10/15 “Emergency,” 351

10/17 “The Year of Getting to Know Us,” 193

10/22 Self Assessment Part I Due

10/24 Prompts Packet Entry Due

10/29-11/19 Workshop

11/21 Full Length Stories Due

11/26 Story Journals Due

11/26-12/5 Small Group Workshops

Finals Day Self-Assessment Part II due

Your Name___________________________________________________________________English 343

On a scale of 1-10, rate the time/effort you estimate each student put into your workshop critique. Use the back of this sheet for further comments, if necessary.

1. Armstrong, Mikel

2. Biers, Kelly

3. Brun, Lucas

4. Detloff, Megan

5. Engler, Aaron

6. Erickson, Justin

7. Hickey, Janel

8. Hoffmann, Charlotte

9. Jenkins, Jason

10. Johnson, Adria

11. Losasso, Angela

12. Martin, Tim

13. Miller, Amy

14. Moeller, Heather

15. Mustapha, Adebayo

16. Natale, Richard

17. Nerison, Bobbie

18. Schmitt, Daniel

19. Urlacher, Emily

20. Voelker, Marcy

21. Wagner, Sarah

22. Wayne, Tiffany

23. Wilberding, Tamara

Saturday, August 18, 2007

Good Thunder Calendar

Visiting authors

2007-08-16

Published in The Free Press, Mankato, MN, 8/16/2007

Rick Robbins, director of the Good Thunder Reading Series, has announced the 2007-08 lineup of visiting authors to Minnesota State University.

Here’s a look at the schedule.

Sept. 13 — Beth Ann Fennelly, poetry.

Oct. 11 — MSU alumni reading with Robert David Clark, fiction, Gwen Hart, poetry, and Thomas Maltman, fiction.

Nov. 1 — Robert Wright Minnesota Writer Residency featuring Luke Rolfes (fiction), winner of the Robert Wright Award, and Marie Myung-Ok Lee, fiction/ young-adult fiction.

Nov. 29 — Deborah Keenan, poetry.

Feb. 7 — James Armstrong, poetry.

Feb. 28 — MSU faculty reading with Candace Black, poetry/creative nonfiction, Robbins, poetry, and Roger Sheffer, fiction.

March 25-28 — Eddice B. Barber Visiting Writer Residency featuring Tom Franklin, fiction.

April 17 — Leigh Allison Wilson, fiction.

Fall 2007 GRADUATE Form and Technique/English 640

English 640 E-Hours: T&F 9-12

Email: diana.joseph@mnsu.edu Office: Armstrong 201L

dianajosephsyllabi.blogspot.com Phone: 389-5144

Form and Technique in Prose

This course examines the technical underpinnings of fiction and nonfiction genres. Through lectures, readings, class discussions, imitation exercises, and workshops, we will study the relationship between form and content. Specifically, we’ll pay attention to issues of craft including point of view, characterization, setting/place, tone, style, imagery, structure, plot and theme.

Required Texts

Almond, Steve, Candy Freak.

Anderson, Laurie Halse, Speak.

Davis, Amanda, Wonder When You’ll Miss Me

Haddon, Mark, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time.

Kundera, Milan, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting.

Martone, Michael, ed., The Scribner Anthology of Contemporary Short Fiction.

Satrapi, Marjane, Persepolis.

Sedaris, David, Dress Your Family in Corduroy and Denim.

Assignments

1. Craft Analysis=25%

Over the semester, you’ll write six craft analyses; which six texts you write about is up to you.

This assignment requires close analysis of how a text is crafted, but the technique studied is up to you. You might want to examine the release of information in a story’s opening paragraph; how a character is created through action or dialogue; how to write a long passage of indirect dialogue; why a writer might opt to write unquoted dialogue; how to establish setting through sound; or through weather; or through geology. You might want to examine how a writer locates a story in time by using a clock; or a calendar; or the seasons; or how a writer manages quick shifts in time; or uses white space. Point of view, establishing psychic distance, creating a voice, moving into or out of a dramatic moment: each requires the writer understand his or her craft.

For each book or story we read, 1.) Decide what technique you want to examine more closely. 2.) Type a specific passage from the text that shows that specific technique in motion. This passage can be as short as a single paragraph or as long as several paragraphs. 3.) Write a short (no longer than ONE single-spaced page) analysis of what the writer achieved and how he/she achieved it.

Bring 2 copies of your passage/analysis to class (one for me, and one to put on the document camera) for an informal presentation.

2. Imitations=25%

Over the semester, you’ll write 6 imitations; which six texts you imitate is up to you.

1.) Type a short passage from the text—be sure to choose a passage that intrigues you, that you think you can learn something from; 2.) write a close imitation of that passage, paying close attention to the author’s voice, tone, style, level of diction, sentence length and sentence structure, but inserting your own content. Bring 2 copies to class (one for me, and one to put on the document camera) for an informal mini-workshop.

NOTE: There are 13 class days; you have 12 assignments. You will turn in either an analysis OR an imitation (not both—which assignment you do on a particular day is up to you) every class day but one. You chose your “free” day.

3. Participation=25%

Participation in not merely showing up for class—that’s called attendance. I define participation as your active engagement with the class demonstrated through thoughtful contributions to class discussion, evidence of preparedness, and helpful feedback during workshops.

4. Form project=25%

What are all the forms a piece of writing can take? There are books and magazines, of course, and broadsides and chapbooks, but there are also take-out menus and checkbook ledgers, classified ads and vanity license plates. Your assignment is to experiment with form, by creating a text whose form reinforces its content in artistic and interesting ways. My only limitation is the text itself must be something I can hold in my hand. Make a copy for each member of our class.

Class Policies

Do the work; volunteer for presentations. Missing more than one class results in dropping a full letter grade. Show up on time. If you’re not here, you can’t participate. No handwritten work will be accepted. All coursework must be completed to pass this class. Late work will not be accepted. Assignments are tentative and subject to change.

Schedule of Events

August 30 Banks, p. 53

September 6 Wonder When You’ll Miss Me

September 13 Speak

September 20 Sontag, p. 569 and Thon, p. 595

September 27 Dress Your Family

October 4 Cunningham, p. 229 and Ford, p. 288

October 11 Candy Freak

October 18 Proulx, p. 521

October 25 The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time

November 1 Braverman, p. 167 and Hansen, p. 338

November 8 The Book of Laughter and Forgetting

November 15 Baxter, p. 131 and Walker, p. 624

November 22—THANKSGIVING BREAK

November 29 Persepolis

December 6 Diaz, p. 244 and Dybek, p. 256

Monday, July 16, 2007

Taxes, weight gain, depression, loneliness—book advances are

like lottery payoffs

by Gillian Reagan Published: June 5, 2007

Tags: Arts & Culture, James Frey, Nathan Englander, Rachel Sklar

This article was published in the June 10, 2007, edition of The New York Observer.

For those who think they have a book inside them just waiting to be written—and,

really, isn't that pretty much everyone?—landing a book contract would be like

winning the lottery. Dreams would come true; doors would open. Anything could

happen.

"You hear about these big contracts coming in, and it whets your appetite," said

Leah McLaren, a columnist for Canada's Globe and Mail, who landed a book

contract with HarperCollins Canada in 2003 for her chick-lit novel, The Continuity

Girl. "You start to think, 'This is my lottery ticket …. It could be optioned for a

movie or become a huge best-seller!'

Indeed, securing a deal with one of the many esteemed editors at publishing

houses like Knopf or Doubleday or FSG seems like fulfilling a kind of New York–

specific American dream. Visions of six-figure contracts, KGB readings and TV

appearances dance through writers' heads. Even better: no more office, no more

boss.

"But then, it could completely disappear and sell five copies," added Ms. McLaren

whose own book was published to little fanfare as a paperback original in the

States this spring. "And you'll never be heard from again. You'll disappear. And

that's the real risk of writing a book."

Slideshow

My Book Deal

Ruined My Life

But just think for a minute, by way of comparison, if a book contract is a lottery

ticket …. Evelyn Adams, who won $5.4 million in the New Jersey lottery in 1985

and 1986, now lives in a trailer. William (Bud) Post won $16.2 million in the

Pennsylvania lottery in 1988, but now survives on food stamps and his Social

Security check. Suzanne Mullins, a $4.2 million Virginia lottery winner, is now

deeply in debt to a company that lent her money using the winnings as collateral.

Could such doom await lucky-seeming, envy-enspiring book writers?

Look at Jessica Cutler, a.k.a. Washingtonienne, the D.C. sex blogger who was paid

a six-figure advance for her novel, based on the experiences she chronicled on her

blog. Suffering under the weight of a lawsuit from an ex-boyfriend, who claims to

have been humiliated by her writing, she has now filed for bankruptcy. She can't

even pay her Am-Ex bill.

Then there are the truly epic downfalls of authors like James Frey, whose

fabricated memoir caused his life (and his seven-figure two-book deal with

Riverhead) to shatter into a million little pieces. Now he's writing two novels

without a contract and posting on the blog and message boards on his Web site,

bigjimindustries.com—the literary equivalent of living in a trailer park.

And even before the potential post-publication humiliation, there's deadline

pressure; crippling self-doubt; diets of Entenmann's pastries and black coffee; self-

made cubicles structured with piles of books, papers and unpaid bills; night-owl

tendencies; failed relationships; unanswered phone calls; weight gain; poverty;

and, of course, exhaustion.

So forget the American dream! Getting a book deal seems more like a nightmare.

In 2002, Daniel Smith, a former Atlantic Monthly staff editor, received the news that he'd gotten a book contract for Muses, Madmen, and Prophets: Rethinking the

History, Science, and Meaning of Auditory Hallucination in a sweltering phone

booth at the MacDowell Colony, an artists' retreat in woodsy New Hampshire.

"There was no cell-phone reception at the time, so you had to get into these poorly

ventilated—meaning there was no ventilation—phone booths. You sweat like a pig

in there, and that's how I got the news. And it was extremely exciting," Mr. Smith

told The Observer.

Mr. Smith's book was inspired by the experiences of his father, an attorney who

was ashamed that he heard voices in his head. He passed away in 1998. "I basically

signed up to think about my father and his most painful secret every day for the

next three years. I basically could sign myself up for mourning every day for three

years, which is really not a fun way to spend someone's life," Mr. Smith said.

"Thinking about insanity every day for many years also is very uncomfortable,

because it's like thinking about death—it's one of our two greatest fears."

At one point, said Mr. Smith, the writing was so miserable, "I thought about getting

into painting houses or digging ditches, doing anything other than writing—

making watches or something like that."

Mr. Smith faced the problem that many authors struggle with: being stuck with

their subjects for one, three, even 10 years at a time.

"I want this woman out of my life so much it's ridiculous," said Michael Anderson,

55, who has been researching and writing a book about the playwright Lorraine

Hansberry for HarperCollins since 1998. "It has been, in essence, 10 years, and

sometimes it seems like, 'My God, why isn't this thing done yet?' But at times I

think, 'My God, it's only been 10 years.' I never understood why biographies took

so much time; now I'm in awe that any of them get finished."

When he received his contract, Mr. Anderson was working full-time as an editor at

The New York Times Book Review, a job he had for 17 years. He figured he would

try to take four years to finish the book and publish it by his 50th birthday. "But

that was just naïve," Mr. Anderson said.

He left The New York Times in 2005, sequestering himself in his Washington

Heights apartment to devote himself to the book.

For months, each night, he would be startled from his slumber at 3:30 in the

morning in the midst of a thought about Hansberry. "She's a nice woman, but I

don't want to be with her all the time," Mr Anderson said.

Nathan Englander spent close to a decade on his second novel, The Ministry of

Special Cases, released this April. "I was getting upset about all the articles—you

know, 'After a decade of silence … ,'" Mr. Englander, 37, said in an ominous tone

during a phone interview.

"Now I look around and wonder—it's hard to remember who I was all those years,"

Mr. Englander added. "I don't care about anything when I'm in the work; nothing

else matters at all …. People I lost touch with, I'm trying to get back to. I'll write

them, 'Thank you for your letter in 1999. Here's what's been going on.' You work

your way through to get familiar with normal life."

Aside from losing touch with friends, Mr. Englander also struggled with everyday

life.“I look down and see that I’m only wearing one shoe,” Mr. Englander said in a

recent interview with the blog Bookslut. “Recognizing it, I think, How can I walk

around like this? Why would I walk around with only one shoe? … Why isn’t that

shelf organized, or why didn’t I write that person back or … I can’t understand

why the person that is me didn’t do these things. And to that question my mother

responds, ‘Because you were like a tortured madman working on this book,’ and I

remember and say, ‘Oh, yeah, that’s why.’”

“Spouses get very jealous of the biographer’s subject, because it really is what you’

re thinking about all the time,” Mr. Anderson explained. “I’ve often thought that if

I were married, my wife would’ve sued for divorce.”

The freedom of setting one’s own schedule, of course, is another gift of the book

contract—for some, it’s the very motivation to pitch a book in the first place. Work

for a few hours, go to yoga, work a little more, eat a sandwich …. It’s a fantasy of

independence, without daily or weekly deadlines imposed from above, without

being picked at by your nosy co-worker. But then…You miss the co-worker: the

ruminations on last night’s Sopranos at the coffee machine, the bitching about

deadlines over lunch. You even long for their Z100 sing-alongs and screeching

renditions of “Since U Been Gone.”

“I found, when I quit The Times, that the biggest problem is loneliness,” Mr.

Anderson admitted.

“Basically, I was giving myself panic attacks in the beginning,” said Ms. McLaren,

who took a leave of absence from her column-writing job to move to an isolated

farmhouse outside Toronto and write her novel in solitude. “As a newspaper

writer, people were always walking over to your desk and being like, ‘Where is it?

How’s it coming?’ All that was taken away—there’s no deadline.”

And then there’s the self-loathing.

“You’re not letting people read it as you write it. Nobody has ever read what you’

re doing. It could be terrible. It could be brilliant. And you start to think, ‘Oh God, this is a complete piece of shit that couldn’t be published—nobody is going to read it.’ But then you have a sandwich and go, ‘I am a genius and I’m going to win the Booker Prize.’”

Rachel Sklar, 34, the media and special-projects editor for the Huffington Post,

barricaded herself her in Lower East Side apartment to work on her book, Jew-ish:

Who We Are, How We Got Here, and All the Ish in Between, a humorous

“guidebook on being a contemporary Jew,” according to Ms. Sklar. “It’s not like

you can pack all that into a pamphlet if you’re going to do it right. You can’t just

wing a chapter on the Talmud.” (Originally due in mid-February, the book’s

deadline has since been pushed twice—once to May and now to mid-September.)

Ms. Sklar took six weeks off from her blogging job to uniform herself in fuzzy

sweatpants, tie her hair into a bun, surround herself in books from the library and

Amazon.com, guzzle Diet Coke and immerse herself in Jewry.

“The stack of books kept me where I was. I wasn’t going out, I wasn’t shopping ….

I berated myself and may have had a few meltdowns. Well, I definitely had a few

meltdowns. But you know, a friend of mine came over at 1:30 [after] a movie

premiere with a six-pack of Diet Coke and a box of cupcakes, and it was the

greatest pick-me-up ever.”

“The interesting thing is that it’s kind of freeing when you have a real good excuse

to tell people no,” said Anna Holmes, 33, the current managing editor of Jezebel, a

Gawker-sponsored female-centric blog, and editor of Hell Hath No Fury: Women’s

Letters from the End of the Affair. “But there was also that fear that the more I said no, at the end of the whole thing I wouldn’t have any friends left.”

Ms. Holmes stayed bundled in her apartment for about a year between 2001 and

2002, leaving her job as a writer at Glamour to cobble together the book.

“If you have an office job, at least it’s walking to and from the subway every day.

When you sit in your house, you seriously gain weight,” Ms. Holmes said in a

phone interview from her Long Island City apartment. “I’m eating my Greek

yogurt and steamed vegetables—I’m trying to be good about what I’m eating. But I’

m still like, ‘I’m getting really soft.’ My idea before the book came out was that I

was going to diet, because I had gotten flabby, so that I’d look better to promote it. But that didn’t happen. I was quote unquote dieting for I think two weeks, but I

just couldn’t do it.”

After all the months of writing, editing and wrangling permissions to reprint

letters, Caroll & Graf released the book in August 2002. But the last thing Ms.

Holmes wanted to do was celebrate the publication.

“I was really tired. I wasn’t so much physically tired, I was mentally tired. At the

exact moment I was supposed to be promoting it, the last thing I wanted to do was

talk about it. I had to get all excited about this thing that I had just given birth to. It was like postpartum depression…

“I had a hard time getting myself back into my quote-unquote normal life, because

I actually started enjoying my [own] company so much and the solitude of it all. I

didn’t even want to go out,” Ms. Holmes continued. “I still tend to kind of want to

be at home and read and, you know, [become] a cat lady, with my cats.”

And what about that holy grail—the advance? Even the smallest advance can be

justified to death as the ticket out of your office job or bartending gig. But is the money that publishers pay most writers enough to make the suffering worth it?

That money, of course, isn’t just for rent and ham sandwiches and Oreos.

It’s also for the sky-high freelance taxes (about 37 percent of any untaxed income

will be commandeered by Uncle Sam), agent’s fees, fax and copy tabs at the library,

travel for research trips and any other number of things. Think about it: $100,000 is actually more like $65,000 after taxes—not bad. But then there’s the 15 percent

agent’s cut (another $15,000), leaving you about $50,000. For a year, that’s a livable salary. But once other book expenses are taken into account—like permissions, travel, copies and the like—you’re looking at a modest pile rather than a mountain. There’s really not much left to enjoy—especially if your work stretches on for years.

“When I hear a book deal, I think, ‘Oh, that person made a 100 grand.’ When I have

a low-five-figure advance, I call it, like, a small gift, I suppose,” said Ms. Holmes. She also learned that her publisher wouldn’t pay for the rights to print the breakup letters she wanted to include in the collection. “The advance I got was not money that I could live on; it was money that had to be used to pay permissions for the book,” she said.

Although Mr. Smith said he was able to survive on his advance, he admits that

those six-figure deals can quickly dwindle away over the three or four years it

takes to write a book. “You’re basically making 30 or 40 grand a year, and that’s

not that great of a salary …. It’s really not as much as it seems. These numbers can

be very deceptive.”

Yet, still, the dreamers dream. Brendan Sullivan, 25, moved to New York after

studying creative writing at Kenyon College in Ohio. He hasn’t landed a book deal for his novel, but is determined to find a publisher.

“Writing has ruined my life and cost me many, many girlfriends,” he wrote in an e-

mail. “I have thrown away several careers and one college degree to spend my

time working in bars, D.J.’ing in bars and drinking my rejection letters away. I

wouldn’t wish this on my worst enemy, and I’ve made many of them since I started

…. I also abandoned my agent with words harsher than those I’ve saved for lost

loves.”

Mr. Sullivan has held 27 jobs to support his writing career, from selling chapstick

on the street to being a night guard in an art gallery (“That was my favorite job

ever, because I just sat in a chair and read novels all day,” Mr. Sullivan added.)

He is currently working on his second novel. His first one, well, “There are eight

drafts of it—they’re in my basement right now,” he said in a phone interview from

his Fort Greene apartment. He trashed the novel after he got into a public fight

with his first agent and decided to start anew. “You have to learn how to suppress

your gag reflex in order to get anything out. Like in love, you make a lot of

mistakes and you learn from them.”

Indeed, despite the heartbreak, the loneliness, the trashed drafts, the rejected

proposals, writers will continue to reach for the golden ticket, the fulfillment of

their American dream.

“In terms of the most joyous life to have in the world, in terms of pleasure

receptors, it might be like being a heroin addict: It’s the most pleasurable thing that you could choose, if you have that constant access,” said Mr. Englander, before

hanging up to head to the coffee shop and write. “I’ll say, ‘Oh, yeah, it almost

killed me,’ but I’m saying that in the most positive way, because it’s all I want to

do.”

More... http://www.nyobserver.com/2007/my-book-deal-ruined-my-life

Wednesday, March 21, 2007

Reading list for Form and Technique (English 640) Fall2007

Almond, Steve, Candy Freak, Harcourt 0156032937

Satrapi, Marjane, Persepolis, Pantheon 037571457X

Sedaris, David, Dress Your Family in Corduroy and Denim, Little Brown 0316010790

Haddon, Mark, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time, Knopf 1400032717

Anderson, Laurie Halse, Speak, Penguin 014131088x

Martone, Michael, ed, The Scribner Anthology of Contemporary Short Fiction,

Scribner 0684857960

Kundera, Milan, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, Harper Perennial 0060932147

Tuesday, March 20, 2007

The class stresses close, careful reading (as a group we'll compile a class text) but it also requires intensive writing. During the first half of the class, you'll write a thousand words a day, five days a week. Topics for writing will come out of prompts; each writer will be responsible for providing a week's worth of prompts.Every two weeks, we'll assemble a packet of these exercises. You should turn in the prompt you find most dynamic or intriguing, the one you're most excited about pushing further. We'll discuss your thousand word piece with an emphasis on craft, but also with the intention of locating the material's potential. Questions for discussion may include What is this piece's emotional center? What seems to be at stake? What are the possibilities for metaphor? For conflict? Based on what's here, who is the narrator?

During the second half of the course, we'll work toward finding connections between and among various prompts as a way to juxtapose unexpected images, build characters and theme, find structures, and develop plots.

This workshop is appropriate for short story writers who'd like to generate new ideas for stories, develop stories-in-progress, or experiment with flash fiction. It's also appropriate for novelists interested in using the prompts as a way to develop their characters, themes, or plot points. Poets and nonfiction writers interested in writing fiction are more than welcome.

Friday, March 9, 2007

Thursday, March 8, 2007

Granta offers up their list of the Best Young American Novelists

Granta also defines "novelist" differently than I might because some of the writers on their list haven't written novels (though they may be working on novels-in-progress.) I don't know yet what I think about this. I think it's good that short story writers aren't excluded from receiving recognition from a prestigious publication, but then I also think stories aren't novels. Story and novel are different, not the same at all. When my story collection came out, nothing irritated me more than hearing someone ask was I working on a novel, when would I have a novel out. I don't think of story as practice for novel; I think if anything, story is closer to poem. But mostly, I think story is its own kind of art.

I've been reading this Truman Capote biography. When his work first began to appear in the New Yorker and the Atlantic Monthly during the 1940's and 50's, the public read stories and talked about stories the way they watch and talk about movies today. It's hard to imagine.

Click here for the Granta list.

Monday, February 26, 2007

The Top Ten: Writers Picks Their Favorite Books

Here's my current--and always evolving--list, in no particular order:

1. The Book of Laughter and Forgetting by Milan Kundera

2. The Times Are Never So Bad by Andre Dubus

3. Birds of America by Lorrie Moore

4. Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell

5. Wise Blood by Flannery O'Connor

6. The Complete Short Stories by Flannery O'Connor

7. As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner

8. Childhood by Harry Crews

9. The Orchid Thief by Susan Orlean

10. Dress Your Family in Corduroy and Denim by David Sedaris

Friday, February 23, 2007

An excerpt:

The issue is more than just savoring literary experience. I am suggesting that there is more than meets the eye in reading, literally. If we attend to the time of reading, we might notice that our relationship to a literary work changes over time. One consequence is that we begin to be charitable to "bad" readers, whether they are our students, our acquaintances, or our former selves. Most important, though, we learn to drop the idea that we can neatly distinguish good from bad reading because we realize that, at some time in the past, we were not up to reading a particular work. Or perhaps we see that while we missed a great deal, we did respond strongly to parts of the work. It begins to make sense, then, to track our career with a certain work, in order to open it up as literature.

Keats gave us a key insight into reading in his poem "On First Looking Into Chapman's Homer," about reading the English poet and dramatist George Chapman's translation of Homer's epics. As often as he had read Homer, Keats wrote, "Yet did I never breathe its pure serene/Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold."

I have increasingly come to believe that the key to reading is rereading. Paradoxically, rereading a literary work is not a quick business, but usually slower than the first time round. We learn that the first time we read too fast, and in a complicated feedback mechanism what was deeply buried in the text can emerge.

To read this piece (slowly and more than once) in its entirety, click here.

Tuesday, February 20, 2007

Monday, February 19, 2007

Thursday, February 15, 2007

Sunday, February 11, 2007

Saturday, February 3, 2007

No writer means more to me

O’Connor’s short stories and novels are set in a rural South where people know their places, mind their manners and do horrible things to one another. It’s a place that somehow hovers outside of time, where both the New Deal and the New Testament feel like recent history. It’s soaked in violence and humor, in sin and in God. He may have fled the modern world, but in O’Connor’s he sticks around, in the sun hanging over the tree line, in the trees and farm beasts, and in the characters who roost in the memory like gargoyles. It’s a land haunted by Christ — not your friendly hug-me Jesus, but a ragged figure who moves from tree to tree in the back of the mind, pursuing the unwilling.

For more, click here.

Tuesday, January 30, 2007

An excerpt:

Interviewer: Perhaps not only a better memory, but a clearer vision as well? Robert Olen Butler said recently that what an artist is supposed to do is not avert his eyes.

Hannah: That’s true. Those that don’t avert their eyes are the real artists. It is concentration, that’s what Dostoevsky said. Concentration is what the artist is about: he can look, and look, and look, and look. He carries no brief. He will tell you everything he sees. This sensibility will overcome every tendency to capsulize or moralize or philosophize; it is why, despite the themes and philosophy announced in behalf of an author by others, the actual art experience is much more whole. Flannery O’Connor can never be accounted for by her Catholicism. There is something rich and deep and strange in her that just doesn’t get on a theorist’s page—that just does not explain itself by outlines. It’s a special feeling.

I know some writers who really are just above making change, but they can tell a story. It has nothing to do with what will show up on an IQ test. They are just gifted in a certain way—even sometimes as an idiot savant. Writers maybe just stare, like a cow—just staring. Most people don’t stare. A writer is unembarrassed to just keep looking.

Tuesday, January 23, 2007

William Faulkner's Nobel Prize Speech

Our tragedy today is a general and universal physical fear so long sustained by now that we can even bear it. There are no longer problems of the spirit. There is only one question: When will I be blown up? Because of this, the young man or woman writing today has forgotten the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself which alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat. He must learn them again. He must teach himself that the basest of all things is to be afraid: and, teaching himself that, forget it forever, leaving no room in his workshop for anything but the old verities and truths of the heart, the universal truths lacking which any story is ephemeral and doomed--love and honor and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice. Until he does so, he labors under a curse. He writes not of love but of lust, of defeats in which nobody loses anything of value, and victories without hope and worst of all, without pity or compassion. His griefs grieve on no universal bones, leaving no scars. He writes not of the heart but of the glands.

Until he learns these things, he will write as though he stood among and watched the end of man. I decline to accept the end of man. It is easy enough to say that man is immortal because he will endure: that when the last ding-dong of doom has clanged and faded from the last worthless rock hanging tideless in the last red and dying evening, that even then there will still be one more sound: that of his puny inexhaustible voice, still talking. I refuse to accept this. I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail. He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance. The poet's, the writer's, duty is to write about these things. It is his privilege to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honor and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past. The poet's voice need not merely be the record of man, it can be one of the props, the pillars to help him endure and prevail.

Monday, January 22, 2007

Zadie Smith, on writing

...somewhere between a critic's necessary superficiality and a writer's natural dishonesty, the truth of how we judge literary success or failure is lost. It is very hard to get writers to speak frankly about their own work, particularly in a literary market where they are required to be not only writers, but also hucksters selling product. It is always easier to depersonalise the question. In preparation for this essay I emailed many writers (under the promise of anonymity) to ask how they judge their own work. One writer, of a naturally analytical and philosophical bent, replied by refining my simple question into a series of more interesting ones:

I've often thought it would be fascinating to ask living writers: "Never mind critics, what do you yourself think is wrong with your writing? How did you dream of your book before it was created? What were your best hopes? How have you let yourself down?" A map of disappointments - that would be a revelation.

Map of disappointments - Nabokov would call that a good title for a bad novel. It strikes me as a suitable guide to the land where writers live, a country I imagine as mostly beach, with hopeful writers standing on the shoreline while their perfect novels pile up, over on the opposite coast, out of reach. Thrusting out of the shoreline are hundreds of piers, or "disappointed bridges", as Joyce called them. Most writers, most of the time, get wet. Why they get wet is of little interest to critics or readers, who can only judge the soggy novel in front of them. But for the people who write novels, what it takes to walk the pier and get to the other side is, to say the least, a matter of some importance. To writers, writing well is not simply a matter of skill, but a question of character. What does it take, after all, to write well? What personal qualities does it require? What personal resources does a bad writer lack? In most areas of human endeavour we are not shy of making these connections between personality and capacity. Why do we never talk about these things when we talk about books?

Reading the rest is worth your time.

Click here.

Saturday, January 20, 2007

A Review of Norman's Mailer New Novel

Here's an exerpt:

FOR Mailer, a novelist fanatically committed to the truth, the problem of the ego’s relation to other people has been for many years now the problem of the narrator’s relation to his material. In his eyes, writing must be an authentic presentation of the self.

As Mailer sees it, great writing puts before the reader life’s harshest enigmas with clarity and compassion. “The novelist is out there early with a particular necessity that may become the necessity of us all,” he has written. “It is to deal with life as something God did not offer us as eternal and immutable. Rather, it is our human destiny to enlarge what we were given. Perhaps we are meant to clarify a world which is always different in one manner or another from the way we have seen it on the day before.”

And once you have authentically presented yourself in your writing, you can no longer practice the expedience of concealing yourself as a person. So Mailer the man has — sometimes not happily — transgressed social norms, just as his books have crashed through the boundaries of alien identity and literary genre. Yet for all the cross-pollination between his art and his life, Mailer has always insisted on true art as a form of honest living. The writer, as he once put it, “can grow as a person or he can shrink. ... His curiosity, his reaction to life must not diminish. The fatal thing is to shrink, to be interested in less, sympathetic to less, desiccating to the point where life itself loses its flavor, and one’s passion for human understanding changes to weariness and distaste.”

...

This restless vastness of Mailer’s ambition (“In motion a man has a chance”) is such that his “failures” are seminal, his professional setbacks groundbreaking. His willingness to fail — hugely, magnificently, life-affirmingly — expands artistic possibilities. Then, too, point to any contemporary literary trend — the collapse of the novel into memoir; the fictional treatment of actual events; the blurred boundaries of “history as a novel, the novel as history” (the subtitle of “The Armies of the Night”) — and there is Mailer, pioneering, perfecting or pulling apart the form.

.

Friday, January 19, 2007

An Interview with Michael Martone

An excerpt:

Since you've identified yourself as a formalist, I'm interested in how you define formalism in relation to your own stuff. Just because, reading the textbook definition of "formalism" there seems to be a real resistance to even being conscious of the extrinsic, in terms of the historical, etc. You don't seem to operate that way.

MM: No. When it comes to prose writing. There seem to be a lot of ways prose writing organizes itself, structures itself, gets itself into forms. And there are certain critics, say Bakhtin, who would say that there is no prose form called the "Novel." Instead, it's really made up of a kind of pastiche of all these other forms. You look at the early novels and they're made up of letters, or a diary of man whose trapped on an island, or they're autobiographies, or they're memoirs, or they're histories, or they're travel guides, or they're travel narratives. There's no thing, that is the novel, that is unlike every other kind of prose writing. That the novel itself is made up of all these different kinds of prose writing. So to me to be a formalist is to recognize these various modes of the human organization of language into prose styles. And be able to switch back and forth from one to the other depending upon the context of what you want to do.

So does your work typically evolve from content to a revelation of form? Or do you usually find yourself more fascinated with a particular form?

MM: That's a good question. A chicken-or-egg question. You know, right now a lot of what I'm working on is this book of fours. I was always interested in the four for a quarter pictures, the photo-booth pictures. I had my students do the photo-booth pictures and try to use the four shots to make some kind of narrative. And I began thinking about various fours. So I guess the form itself, or the arbitrary form, sort of leads for me and I'll find ways to connect it. One form, of course, is the narrative form and it has its own structure of ground, situation, vehicle, rising action, etc. etc. If you make the decision that you're not going to tell a story, or be narrative, how you organize becomes more prevalent.

Thursday, January 18, 2007

An Interview with Andre Dubus

Smolens: Is it possible that there's a change, not in fiction, but in the way fiction is perceived?

Dubus: You mean imaginative writing!

Smolens: There seems to be an impatience on the part of some readers.

Dubus: They're sometimes unwilling to grant the writer a certain freedom. I think they are poor readers. I mean, when I read I like to forget my name. I like to experience being another person-I get to love the character, if the writer is good. I learn something, and then I put the book down and I'm me again.I think there are some people who have strong opinions, and they get offended by what a writer says. They seem dictatorial to me. Sean O'Faolain wrote an introduction to a big anthology of short stories, and in essence, he said, "If you don't like a story, consider it your fault. And read it again." Then he went on to explain eloquently why it may be your fault. For instance, you may be in moral shock: these characters may do something you never considered doing.A while back I read about the actress Debra Winger in a profile Tom Robbins did for Esquire. He put it better than this, but the essential question he asked her was, "You're not really beautiful, so why are you so beautiful on the screen?" A hard question, which he stated politely. And her answer was, "The camera picks up the heart. To go before the camera you must open your heart, and get rid of all prejudices, all preconceptions, and be absolutely open. If you had twin sisters appear before the camera-where one did this and the other didn't-the camera would see it immediately." In effect, that was her response. To me, that's what writing is about, and that's what pure reading is about.

Smolens: We've previously discussed that a central problem in writers' workshops can be criticism that merely tells the writer how to rewrite the story, and that some writers bring a piece to the workshop and request just that: they want their fiction written by committee, so to speak.

Dubus: In my workshops we've discussed this, and there have been times when I've learned that I was not the only one who found it difficult to go back to my own work-that's how important this problem can be.In my workshop we started to have difficulties; I had this explosion, then we took the summer off. Then Chris Tilghman came to the house to discuss how we should be when we came back together. If you go into a room with eight or nine very good professional writers and ask them to read your work, you're going to get eight or nine very good ideas, all of which would work. But it wouldn't be your story; it might be a story you could write, but it might not be the story you should be writing.What we worked out for the new workshop-there were a number of new members who joined at that point-was that a writer reading should say, "I just want to hear about this. I'm concerned about the grandmother's character." Or the writer can say, "Go full bore and tell me whatever you want."Some people enjoy a good debate, of course, but I started wondering: what is the reason for two writers arguing about a third writer's work in the third writer's presence? Too often they were arguing for their own ideas. It was exhilarating, but I'm not sure it's always a good idea.

For more click here.

If you haven't read Dubus' collection The Times Are Never So Bad, you need to.

Wednesday, January 17, 2007

Steve Almond's 10 Guiding Principals for Writing About Sex

Steve Almond is the author of two story collections (My Life in Heavy Metal and The Evil B. B. Chow); a novel co-authored with Julianna Baggott (Which Brings Me To You); and a nonfiction book about his passion for candy (Candy Freak.)

Tuesday, January 16, 2007

Saturday, January 13, 2007

Anton Chekhov

Ernest Hemingway

Lillian Hellman

Joan Didion

Vladimir Nabokov

Harlan Ellison

Oscar Wilde

Susan Sontag

F. Scott Fitzgerald

William Faulkner

William Faulkner

William Faulkner

Sinclair Lewis

Norman Mailer

Virginia Woolf

Flannery O'Connor

Alice Walker

English 643 Fiction Workshop Spring 2007

Diana Joseph Office: AH

English 643 Phone: 389-5144

Email: diana.joseph@mnsu.edu Hours: MTWT 11-12 & by appt.

Syllabus/other class documents: http://dianajosephsyllabi.blogspot.com

English 643: Seminar—Fiction Writing

Text

Diogenes, Marvin, and

Assignments See Schedule of Events for due dates

1. Craft Analysis/Presentation=50%

A. Select a story from any edition of Best American Short Stories between 1994—2006. The story you pick should be one you love. Make copies of your selection for everyone in the class—16 copies.

B. Define, then discuss and analyze ONE of the following elements of fiction as it relates to the B.A. story you selected. Support and illustrate claims with specific examples from the text; explain how and why the examples support your claim. Turn in your craft analysis to class on the day of your presentation.

Point of view Characterization Style Structure

Setting/place Tone Imagery Theme

2. Participation=50%

I define participation as your active engagement with the class, demonstrated through evidence of preparedness, and thoughtful contributions to discussions and workshops. Each of you will offer an assessment of your peers’ workshop responses; I will take this into consideration when determining participation grades.

Workshop Philosophy

This workshop differs from traditional workshops.

When we discuss a story, there won’t be talk about what we “like” or “don’t like.” There won’t be talk about what’s “good” or “bad”; there won’t be any value judgments. (This kind of feedback is hugely subjective and frequently confusing—like when six people love it, six people hate it, and one needs more time to think things over.) There won’t be advice on how to “fix” your story. (It’s your story, which means it’s your vision/version of the world, which means you should be the only one who can fix it.) There won’t be suggestions about what you “could” or “might” do. (I’m not interested in talking about writing that hasn’t been written.)

I am interested in what your story is about – the questions it raises, its themes, your artistic vision – and I’m interested in how your story is told, how its form reinforces its content. If writing is a series of choices, then what are the effects of these particular choices? If there’s an infinite number of ways to say something, then why are you saying it in this particular way? Why use first person instead of third person limited? What’s the effect of present tense over past? What are the story’s significant images and how do they create meaning? This workshop centers on describing and interpreting your use of the elements of fiction—and describing how each works with the rest to create unity, a singular effect, a vivid and continuous dream.

This approach demands work that’s more polished and developed than a rough first draft. Do not bring in work that is incomplete—it must have a recognizable beginning, middle and end. If you’re bringing in a chapter from a novel, please provide a brief description of your project. If you bring in sloppy work, don’t be surprised if there’s not much to say about it.

Class Policies

Do the work; don’t miss class; show up on time. Participation is 50% of your final grade. If you’re not here, you can’t participate. If you fail to turn in your story on the day it’s due, you lose your workshop spot. If you don’t come to class on the day of your workshop, it won’t be rescheduled. If you’re not here to give your Best American presentation, you can’t make it up. All coursework must be completed to pass this class. Assignments are tentative and subject to change.

Due Dates

1/24 Copies of your Best American selection due

Nyberg, “Why Stories Fail,” 221; Stern, “Don’t Do This,” 230;

1/31 Workshop story due

Best American—Bigalk and Cole

Surmelian, “Scene and Summary,” 164

2/7 Best American—Davis and Dunnan

Workshop

2/14 Best American—Engesether and Faul

Workshop

2/21 Best American—Hooper

Madden, “Point of View,” 248

Workshop

2/28 AWP

3/7 Best American—Irmen

Workshop

3/14 Spring Break

3/21 Best American—Johnson

Workshop

3/28 Best American—Khoury

Workshop

4/4 Best American—Lacey

Workshop

4/11 Best American—Miller

Workshop

4/18 Best American—Rolfes

Workshop

4/25 Best American—Starkey

Workshop

5/2 Best American—Vercant

Workshop

Name________________________________________________________________________English 643

On a scale of 1-10, rate the time/effort you estimate each student put into your workshop critique. Use the back of this sheet for further comments, if necessary.

1. Bigalk, Kristina M

2. Cole, Antoinette K

3. Davis, Andrew S

4. Dunnan, James W

5. Engesether, Marc R

6. Faul, Jade A

7. Hooper, Catherine A

8. Irmen, Ami M

9. Johnson, Bryan E

10. Khoury, Elysaar

11. Lacey, Kathleen N

12. Miller, Dodie M

13. Rolfes, Luke T

14. Starkey, Danielle M

15. Vercant, Matthew C

.jpg)